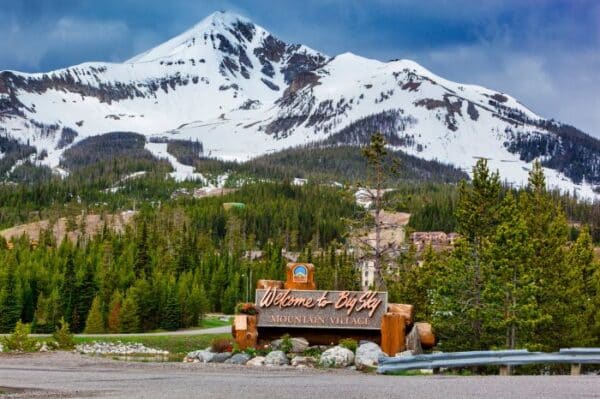

Big Sky, Montana

Montage Big Sky announces its new collection of signature Mountain Homes as an expansion of its residential portfolio. Located within the resort’s 3,530 acres of private forested mountain landscape, Montage Big Sky’s newest residences offer owners and guests an unparalleled experience in one of the country’s most exclusive and pristine wilderness regions.

“The Mountain Homes are an exciting and pivotal addition to the residential portfolio at Montage Big Sky,” says Tina Necrason, Executive Vice President of Residential, Montage International. “As part of our commitment to redefining the art of luxury stays and residential living, we are thrilled to debut these homes as an expansion that truly harnesses the natural beauty and adventure of Big Sky.”

Surrounded by Douglas Firs, Engelmann Spruces, and panoramic vistas of the Spanish Peaks, each of the 15 Mountain Homes is designed by the renowned team of architects at Poss Architecture & Planning, and is available in a choice of five-bedrooms with 5,320 sq. ft. of living space or six-bedrooms with 5,515 sq. ft. Select homes will be available as part of Montage Big Sky’s Residential Rental Program, offering guests the opportunity to enjoy the privacy and comfort of a home while still experiencing the resort’s signature services, including dedicated management, housekeeping, concierge services, and more.

With triple-height floor-to-ceiling glass windows, sleek finishings, light oak hardwood floors, and bright white and cream hues woven throughout, intentional aesthetic elements celebrate the modern mountain lifestyle. Each Mountain Home is designed with expansive indoor and outdoor living spaces that encourage families and friends to enjoy quality time together in an alpine setting.

Situated within the heart of the Spanish Peaks, owners and guests will enjoy direct ski-in, ski-out access, as well as the convenience of nearby hiking, biking, Nordic trails, and other outdoor adventures. After a day of exploration, they can return home to cozy up by the fire, unwind in the sauna, luxuriate in the outdoor jacuzzi, or prepare a meal in a full gourmet kitchen with premium appliances. Bedrooms are thoughtfully spread across multiple floors, including a master suite with a fireplace and private balcony, and offer options for king-sized or bunk bedding in each room. Additional features of the Mountain

Homes include a second living room and entertainment space with a full wet bar, an expansive laundry room, and a ski/mudroom equipped with lockers and boot dryers, offering every convenience for a perfect mountain retreat.

Mountain Home resident owners and guests will enjoy all the amenities of Montage Big Sky, from the expansive wellness services at the 11,000-square-foot Spa Montage with its tranquil indoor pool, to year-round outdoor pursuits with Compass Sports and unique on-site retail offerings. The resort also provides a wealth of dining experiences, including elegant Northern Italian cuisine at Cortina; craft cocktails, local brews, and live music at the lively Alpenglow; and family-friendly fun with bar games at Beartooth Pub & Rec.

For more information about the new Mountain Homes and residences at Montage Big Sky, please visitwww.montage.com/bigsky/accommodations/residences. To learn more about Montage Big Sky, please visit www.montage.com/bigsky/ and follow @montagebigsky.

Weiskopf’s final course opens in MontanaThe par-3 Tom’s 10 channels some of the late hall of famer’s favorite holes from around the world.

Courtesy of Jonathan Finch

Spanish Peaks Mountain Club will open its new Tom’s 10 — the final golf course designed by World Golf Hall of Famer Tom Weiskopf — on July 1. The 10-hole par-3 pays homage to Weiskopf’s favorite holes from around the world.

A member of Spanish Peaks and resident of Big Sky, Montana, Weiskopf designed the club’s original 18-hole championship course and, in his final years, collaborated with longtime partner Phil Smith of Phil Smith Designs on the new par-3 course. Weiskopf died in August 2022.

With increasing membership and the opening of Montage Big Sky on its grounds, Spanish Peaks began looking at options for a new golf course in 2020, an effort led by Ryan Blechta, senior director of grounds and mountain operations.

“Working with Tom on this course was such an incredible experience,” Blechta said. “From our first walk through the woods when he shared his vision till the last time he was on the site a week before his passing, I got to know Tom on not just a professional level, but a personal one, and will always cherish the time spent with him and his wife, Laurie. On behalf of the club, I’m proud to share this course with our members — I truly believe it kept Tom going in his final years.”

Weiskopf frequently visited Blechta in his office on occasion to talk. During one of those visits, Blechta told Weiskopf of the club’s desire to expand and Weiskopf said he knew the perfect location for a par-3 course — a 35-acre site where he liked to walk his dog among the timber, streams and wetlands. Soon, the two were scouting the site on foot with Weiskopf describing potential locations for tees and greens.

The club broke ground on the course in summer 2021. Weiskopf brought in Smith throughout the design and construction process. Frontier Golf was the primary contractor. Construction took three summers because of the complexity of the project and its elevation of more than 7,000 feet.

Diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2020, Weiskopf was undergoing treatment during the initial design and construction of the course. When his cancer returned during the spring of 2022, a second shaper was brought in to speed up the process. Weiskopf was able to work on the course until the week leading up to his death and approved all but the final hole.

Spanish Peaks dedicated the course to Weiskopf as Tom’s 10 — an homage to his favorite par-3 holes from around the world, including the original 18th at the club, seventh at Pebble Beach, 18th at Loch Lomond, eighth at Royal Troon and 16th at Augusta National. Holes range from 90 to 161 yards, and total 1,199 yards. The course has 200 feet of elevation change.

Unique features include a man-made half-acre pond on 4 stocked with more than 1,000 westslope cutthroat trout — Montana’s state fish — a deep bunker at the front right of the fifth green set to Weiskopf’s 6-foot-3 height and an old log cabin from one of Weiskopf’s properties that was reassembled and converted into a comfort station filled with memorabilia from his career donated by his wife.

Greens were sodded with Dominator bentgrass, and tees and rough were sodded with dwarf Kentucky bluegrass. Native areas were hydro-seeded with a custom Rocky Mountain mix that includes wildflowers. Bunkers were lined with Capillary Concrete and have Uniman BB 205 white bunker sand. Cartpaths are poured concrete. Eight bridges were installed to avoid disturbing natural streams and wetlands.

“This new par-3 course really shows off the design principles we used throughout our time working together,” Smith said. “It’s a throwback to a lot of fun things we’ve done in the past. And it was very therapeutic for Tom. Because he lived nearby, he was able to keep his mind off his illness and give the project his personal attention. Being at Spanish Peaks from the inception of the original course till he couldn’t work anymore was such a gift. This final project is a direct reflection of his commitment to his craft.”

Nestled in the heart of the majestic Rocky Mountains, Big Sky, Montana, has been calling to winter enthusiasts seeking the ultimate skiing adventure for generations. Renowned for its expansive landscapes and the iconic Lone Peak, Big Sky visitors have plenty to see and do. Big Sky Resort is the largest ski resort in the United States, and offers skiers and snowboarders vast and varied terrain, a true winter wonderland for all skill levels.

Encompassing over 5,800 acres of skiable terrain and receiving an average annual snowfall of more than 400 inches, Big Sky Resort is a haven for powder enthusiasts. But Big Sky boasts far more than just skiing and boarding, visitors can find unique adventures and experiences year-round!

Many of Big Sky’s outdoor adventures are perfect for bringing your four-legged family members along, who doesn’t love hiking with their dog? These Big Sky accommodations welcome your dog along for the adventure. From cozy mountain lodges to luxury alpine homes, these are the best dog friendly places to stay in Big Sky.

Aspect Big Sky – Katie Aleer

Aspects Big Sky

The new luxury rentals welcome your four-legged friends. Aspects Big Sky is a group of thoughtfully designed houses that sit on 6-acres of land featuring a sauna, fire pit and gorgeous 365 views. Signature homes come with a private out door hot tub. Each home sleeps up to 7 and includes everything, no worrying about doing chores before you leave like some other housing rentals! You can book one home for your Big Sky getaway, or you can book multiple for a memorable group travel experience.

The Wilson Hotel

The Wilson Hotel

Located in the Big Sky town center The Wilson Hotel offers convenience and luxury for guests visiting Big Sky. Take a dip in their outdoor heated pool or relax in the hot tub while you take in stunning views of Lone Peak Mountain. The Wilson Hotel offers guests a free shuttle to the base of the mountain for easy access to skiing and when you return for the day enjoy some après at the Wilson Bar! The Wilson welcomes dogs, you will find treats on the front desk for when you return from a walk.

320 Guest Ranch

320 Guest Ranch

Just 12 miles down the road from Big Sky, 320 Guest Ranch provide guests with a true retreat. Select from a variety of deluxe cabins for you, the family and your dog! Connect with nature on through one of the many activities offered right on-site including horseback riding, fly fishing, or sleigh rides in the winter. For those looking to ski and ride, Big Sky is just a short drive down the road!

Montage Big Sky

Montage Big Sky

Offering ski-in/ ski-out convenience Montage Big Sky aims to wow guests with beauty and a luxury ski experience. Opened in 2021 the resort offers breath taking views of the Spanish Peaks Mountain range. Guests will find little reason to leave, everything they could need or want can be found at the resort, the 139 guest rooms offer modern design and comfort, there is a wide selection or world class dining, and the spa is the perfect place to unwind after participating in one of the many activities offered on-site like snowshoeing, skiing, and more. Montage welcomes your four-legged family members and will work with you to make sure your stay with them is comfortable and relaxing.

The Huntley Lodge

The Huntley Lodge

If you’re looking to stay as close to Mountain Village as possible with your dogs The Huntley Lodge is a great pick! The Huntley Lodge has a down-to-earth alpine feel to it and it’s convenience to the mountain cannot be beat. The Huntley Lodge is the original Big Sky Lodge, reimagined and refreshed for modern comfort. Select rooms are pet friendly so book early to make sure your furry friend can join in on the fun.

From Mauritius To Montana, Forbes Travel Guide’s 2024 Star Award WinnersThe Only Five-Star Hotel Brand

Montage Big Sky, an alpine ski retreat in Southwestern Montana that opened in 2021, picked up its inaugural top rating. The win marked a Five-Star sweep for Montage Hotels & Resorts across its seven properties, giving it the title of the world’s only all-Five-Star hotel brand. The Montage collection spans from Bluffton, South Carolina, to Los Cabos with a strong presence on the West Coast with properties in Sonoma, Laguna Beach and Park City, Utah.

The U.S.-based company is a longtime luxury hospitality purveyor—it celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2023 and boasts the longest-running Five-Star spa. California’s Spa Montage Laguna Beach was the first spa to earn the Five-Star distinction in 2005 and has maintained the rating ever since.

From Beantown to Big SkyHow CrossHarbor Capital’s Sam Byrne revitalized Yellowstone Club and realized a vision for the Big Sky we know and love today.

If you’ve spent much time in Big Sky, you might have run across the name Lone Mountain Land Company. It’s the outfit behind the development of Town Center, Moonlight Basin, and Spanish Peaks Mountain Club. You might also have heard the name CrossHarbor Capital, parent company of LMLC.

But how did a Boston-based private equity firm find its way to the wilds of Montana? And how did that event morph into the visionary community building of Lone Mountain Land Company?

Like so many good things in life, it started with a ski trip.

“I fell in love immediately. The ski experience was so extraordinary.”

Sam Byrne, Cofounder and Managing Partner at CrossHarbor Capital

The year was 2005, and CrossHarbor’s cofounder and managing partner Sam Byrne arrived at Yellowstone Club as the guest of a family friend. “I fell in love immediately,” he recalls. “The ski experience was so extraordinary.” It was also revelatory, because at the time so much attention in the premium ski market was directed toward the likes of Deer Valley in Utah, and Beaver Creek in Colorado. But Yellowstone Club’s 2,200 skiable acres (now 2,900 acres) surpassed both. Byrne likes to cite a comparison with Beaver Creek. Roughly the same size as Yellowstone Club, Beaver Creek does 1.1 million ski visits per year. Yellowstone Club does just more than 70,000.

Byrne enjoyed his visit to Yellowstone Club enough to become a member that same year. As the story goes, Sam’s wife, Traci, agreed to the membership… “as long as you promise you’ll never get involved.” Obviously, things changed.

Before we fast-forward to Byrne’s eventual purchase of Yellowstone Club, let’s rewind a moment. Byrne grew up in Marblehead, Massachusetts, where his mom worked in real estate. When Byrne was 17, he filled in for an agent in his mother’s firm—and made a $1 million sale. From that point on, he was hooked. After graduating from Tufts University in 1986, he learned the ropes of restructuring bad loans for Bank of New England. By the age of 26, he had struck out on his own, starting CrossHarbor Capital Partners in 1992. The firm specialized in real estate, and Byrne had a particular affinity for structuring deals to acquire distressed properties. His passion for racing off-road vehicles and powder skiing are likely related to his career path. Sam Byrne likes calculated risks.

The entrance to Yellowstone Club. Photograph courtesy of Lone Mountain Land Company

Yellowstone Club Rescue

In 2008, Yellowstone Club was in the midst of a messy bankruptcy. The principal owner had taken out a large loan, using the club as collateral. He was being sued by his limited partners and at the same time going through a divorce. The principal asset in the divorce? The overleveraged club.

Despite the financial troubles, of course, Yellowstone Club still had a lot going for it. The setting is one of a kind and the ski experience is too. But more than that, Byrne recognized that the Yellowstone Club needed to coexist with the larger community of Big Sky to thrive. The goal would be to tie the communities and infrastructure together with great people. Byrne never lost sight of that even while the YC was floundering. Remember, this is a person skilled in the art of buying distressed properties. “The more complicated and broken the better,” he says. “As a distressed investor, I have to have conviction around doing things when other people are fearful.”

In engineering the deal that would lead Yellowstone Club out of bankruptcy by July 2009, Byrne also pledged to provide $100 million in working capital. That cash infusion was what got the YC moving forward again.

“Byrne recognized that the Yellowstone Club needed to coexist with the larger community of Big Sky to thrive.”

Robert Earle Howells

Byrne and YC ambassador Scot Schmidt. Photograph courtesy of Lone Mountain Land Company

Restoring Confidence

“When we brought the deal originally, Yellowstone Club was a huge consumer of capital,” Byrne recalls. “It was losing money hand over fist.” Not only that, but the club’s reputation had suffered greatly. “We didn’t expect to generate much revenue those first few years,” Byrne says. That was, in part, because he was committed to making good on the club’s debts. Again, rebuilding the club’s ties to greater Big Sky was paramount.

“Yellowstone Club couldn’t have had a worse reputation,” he says. “So many vendors hadn’t been paid. The club didn’t have good standing in the community. We knew that we wouldn’t succeed in bringing Yellowstone Club and the resort and the budding town together if we didn’t make those partners whole. The debt and ill will extended all over southwest Montana. We needed to build goodwill, not for monetary gain, but because that was and is a core tenet of who we are.”

“We needed to build goodwill, not for monetary gain, but because that was and is a core tenet of who we are.”

Sam Byrne

Sam Byrne speaking at a YCCF fundraiser benefit for the Big Sky community. Photograph courtesy of Lone Mountain Land Company

A key element of the bankruptcy plan was to deliver checks to every single creditor at 100 cents on the dollar. “We knew we couldn’t function in the community if we didn’t get that money to the people who had been working at and building the club,” he says. Byrne hand-delivered a number of those checks.

That “repair and rehabilitate” commitment was the first step to bring YC out of bankruptcy and into profitability and ongoing success. As such, Byrne and CrossHarbor were the driving forces behind the revitalization of Yellowstone Club, but Byrne emphasizes that it wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the club’s original 260 members.

“I went to them and gave them all the right to co-invest in the deal. I said, ‘Listen, you have to be part of the solution here. If every one of you brings one great friend, we not only make the club better, but we get to the break-even operational standpoint.’”

Byrne skiing at Yellowstone Club. Photograph courtesy of Lone Mountain Land Company

With that, CrossHarbor moved into the next phase: product creation. Working with the club’s developer, Discovery Land Company, “We wanted to create ways to get people into custom homes in a very short period of time,” says Byrne. “We did a lot of market study work to create the best possible product.” The emphasis, and Byrne’s personal passion, was on the club’s one-of-a-kind skiing. Delivering the best possible ski experience meant investing in snowmaking, new lifts, a 30 percent expansion of skiable terrain, and everything necessary to nurture the club’s trademark offering: the ability to ski right up to a lift, get on immediately, and savor the mountain’s world-class snow.

But the restoration of Yellowstone Club required more than a cash infusion. It required a face. After so many years of chaos, the homeowners, members, employees, and contractors needed to see someone steering the ship. Between Mike Meldman from Discovery and Sam Byrne from CrossHarbor, the people in charge committed to being on site every weekend. For the first five or six years—nearly every weekend, every holiday, every school break—Sam Byrne and his family were on the ground in Big Sky.

That invest-and-reinvest strategy continues. “We added summer experiences and built a tremendous amount of infrastructure for retail and ski operations,” says Byrne. “That includes a $40 million event barn and performing arts center. But more than that, we were no longer an anonymous entity. We put forward a name and a face and the accountability that comes with it. From that point forward, I stopped looking at CrossHarbor, and later Lone Mountain Land Company, as developers of distressed properties, but as people helping to build neighborhoods and towns. We wanted to develop a sense of place. You do that by putting great people on the ground. ”

Today, Byrne looks back on that phase with pride: “The membership invested in our success both emotionally and financially. What I gave back to them was infrastructure they never expected. But probably more important than that, Yellowstone Club stopped feeling like an island separate from Big Sky. Instead of just a vacation getaway, it began to feel like home.”

Beyond The Club

Let the above story serve as preamble because it was just the beginning of CrossHarbor’s presence in Big Sky. “As we were building out Yellowstone Club,” says Byrne, “we saw the need for more amenities outside the gates: expanding airlift into Bozeman, getting a downtown built in Big Sky, building a hospital, developing community housing, connecting neighborhoods with trails, rehabilitating second-growth forest, protecting the water and the views… all of those needs led us to making significant additional investments in Big Sky.”

In looking beyond Yellowstone Club, Byrne once again recognized the need for a strong local face and presence. CrossHarbor had succeeded in engineering the renaissance of Yellowstone Club, but the shared vision for the broader community required a different kind of presence. CrossHarbor, which had purchased both Spanish Peaks and Moonlight Basin from bankruptcy in 2013, was and is a real estate investor, not a developer or marketer or community builder.

“In 2014, CrossHarbor created Lone Mountain Land Company to help guide thoughtful and sustainable development throughout Big Sky. That’s when we went from being investors and financiers to developers and community builders.”

Matt Kidd, LMLC Managing Director

In 2014, CrossHarbor created Lone Mountain Land Company to help guide thoughtful and sustainable development throughout Big Sky. It was, says LMLC Managing Director Matt Kidd, “a monumental step forward.” Kidd, who was already part of CrossHarbor’s Big Sky/Yellowstone Club team at the time says, “That’s when we went from being investors and financiers to developers and community builders. Yellowstone Club became part of the broader community, and Spanish Peaks and Moonlight Basin followed. That was good for the foundational investment over the long-term. But more importantly it’s good for Big Sky. Without those communities we don’t have the resources to build parks and hospitals.”

Moonlight Basin Lake Camp with views of Lone Peak. Photograph by Zak Grosfield

A lively Farmers Market in Town Center. Photograph by Joe Esenther

If real estate investors typically take a short-term view built around profit, as a community builder, Lone Mountain Land Company’s vision is something else entirely. “We take the long-term view,” says Kidd. “If we can help Big Sky grow as a community, then everyone benefits. There’s not a single challenge in Big Sky we’re not actively addressing.”

For Kidd, the formation of LMLC was also an opportunity to build a local team—and in the process become a local himself. “I had been with CrossHarbor since 2009, and in fact I was on a plane to Big Sky on my third day on the job. I’d never been to Montana before. But the first time I drove up the canyon, I knew Montana was going to change my life.

“I bought the first house that Lone Mountain built in Spanish Peaks,” he recalls. “By 2014, it was becoming clear that Big Sky would be my focus and my future.” Kidd and his family started living in Big Sky all summer and winter, but Kidd was still spending time in CrossHarbor’s Boston office. In 2019, he became a full-time Big Sky resident. “I live here and love living here. I devoted a huge amount of my personal and professional life to this place. I enjoy Montana. I drive my kids to baseball and soccer games just like every other Montana parent.”

Having witnessed how taking accountability and joining the community changed Yellowstone Club through Byrne’s initiative, Kidd set about building a Lone Mountain Land Company team of like-minded folks who would put Big Sky first because they too were raising kids and volunteering locally. “Today,” says Kidd, “Sam and I are just part of that team. Everyone at Lone Mountain Land Company takes accountability. We are committed to maintaining the qualities that make Big Sky special. We’re all-in. We live in the community we’re working in, so it’s natural for us to be stewards of the land, to always try to do the right thing.”

The ongoing development of Town Center is a clear example of this dedication, says Byrne: “We saw the community needed more food and beverage outlets, more retail activity, gathering places, and a community center, as well as community housing, conventional housing, and hotels.”

Looking back, Byrne acknowledges that getting to this point entailed many challenges, ranging from financing to public relations, and the simple fact that almost every project and advancement took longer than anticipated. But when he is out on the mountain with his family, he’s reminded of what drew him to Big Sky in the first place: what is now 9,000 acres of skiable terrain when you combine Big Sky Resort with the Yellowstone Club. “We will always deliver on the experience, on being the Augusta of skiing, and delivering an equivalent experience in summer. But now we’re also delivering on a dream that I didn’t originally envision. We aren’t just building world-class resort communities and infrastructure, we’re working with everyone in Big Sky to turn what was once a smattering of isolated developments into a hometown.”

“We aren’t just building world-class resort communities and infrastructure, we’re working with everyone in Big Sky to turn what was once a smattering of isolated developments into a hometown.”

Sam Byrne

Panoramic view from Moonlight Basin. Photograph by Jonathan Finch

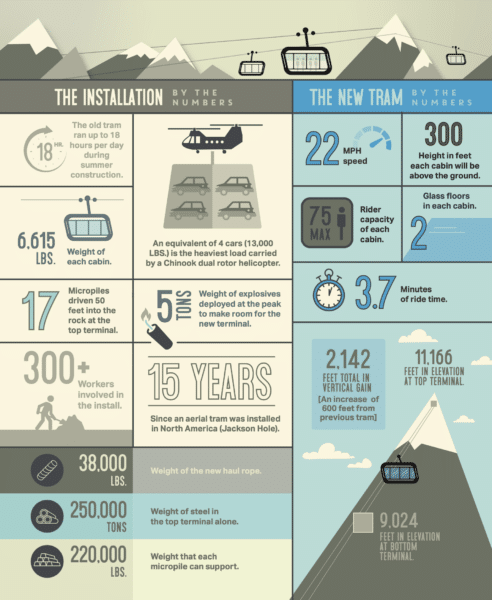

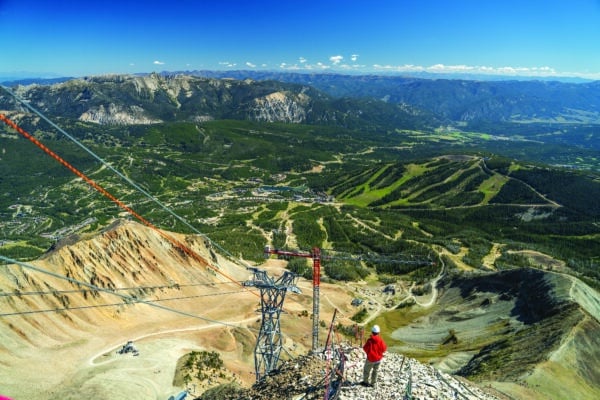

The Tram Is Dead. Long Live The Tram.

After 27 years, the iconic Lone Peak Tram has been decommissioned, making way for its heir, which is also one of the boldest lifts in North America.

The most anticipated development in the North American ski world this winter is the grand opening of the new Lone Peak Tram, which will deliver more skiers (conditions dependent) and sightseers up the hill in faster and more comfortable cabins. The original tram changed the sport of skiing by ushering in a renaissance of steep skiing. The new iteration ensures the tradition lives on, while ramping up the quality of the experience. “When the first tram went in, our messaging was that Lone Peak was America’s Alp,” says Big Sky’s President and COO, Taylor Middleton. “When we took over operations of the Moonlight side, we celebrated the ‘Biggest Skiing in America.’ Both of those visions still hold true, but the new mission is to improve the quality of the ski experience for everyone. Nothing exemplifies that more than the new Lone Peak Tram.”

What it Means to “Manage to Snow Capacity.”

The original tram was small by design. John Kircher, the resort operator at the time, knew that skiers could safely enjoy the hairball terrain off Lone Peak, but he also knew that—in certain conditions—if too many skiers descended the same slopes the snow would bump up, get pushed down the hill, or burnish to a risky glaze under constant edging.

Taylor Middleton, President and COO of Big Sky Resort. Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

John Kircher passed away in 2023 from cancer. But although the new tram’s official capacity is 75 skiers—60 more than the old tram—don’t expect to see that many loading. That’s because the number of skiers allowed in each car moving forward won’t be determined by revenue models or some notion of customer service, but by what Taylor Middleton, Big Sky’s President and Chief Operating Officer calls “Snow Capacity.”

Although the tram’s official capacity is 75 skiers-60 more than the old tram-don’t expect to see that many loading.

Taylor, who is the only current Big Sky employee that was on the ground for the original installation, shares John Kircher’s vision: “When the original tram went in, people told us the terrain was too dangerous, the avalanche hazard too high,” says Middleton. “But working with our patrollers and snow safety teams we quickly figured it out. That management style will not change. We expect to load 25 skiers and 10 scenic riders per cabin on most days.”

Equal parts engineer, rigger, and alpinist, building a tram requires rarified skills by workers. Here, a team from Garaventa, the Swiss subsidiary of Doppelmayr that specializes in aerial trams, feeds a pilot line for the track rope. “That is Cedric and Christoph Hohenegger pulling the pilot rope for the 2nd track rope manually,” says Big Sky Resort’s Construction Project Manager Jas Raczynski. “We were not able to pull the pilot line with the helicopter due to scheduling conflicts that day, but these dudes wanted to stay on schedule.” Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

When the original tram was installed, people in town could see the glow from extreme skier/alpinist/welder Tom Jungst’s torch in town each evening. But technology changes with the times. The new tram was custom engineered and prefabricated in Europe. It went up bolt by bolt on-site like an erector set. Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

It’s hard to prove a negative, but it’s a good bet to say that for two years, this was the highest crane operating in the word. The heaviest crane piece for the Chinook helicopter which hauled it up was 9,000 pounds. “Setting up the tower cranes was the most difficult step in the entire installation,” says Chad Wilson, Big Sky’s Vice President of Construction. Photograph by Jonathan Stone

“Setting up the tower cranes was the most difficult step in the entire installation.”

Chad Wilson, Big Sky Resort’s Vice President of Construction

At these slope angles, everything must be anchored. These threaded bars will support the power lines. Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

The old tram ran on a continuous span—which explained some of the sway in the wind. The new tram sports a stabilizing midway tower, and computer assisted docking to ease the entry. Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

Installing a track rope for a lift is never easy, but the elevation and exposure on Lone Mountain amplified the difficulties. The first step is for a helicopter to lift a 10mm thick pilot line that gets manually fed through the bogies. That line, in turn, gets spliced into a 16mm cable which is pulled through. The process continues with a 22mm cable pulling a 32mm before the final 48mm track rope is threaded through the system. Each gauge of rope takes five days to wind for what amounts to a 25 day process. A highly skilled helicopter pilot made the pilot line stage go smoothly. Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

Everything depends on mountain weather and mountain snow. If the wind is scouring the alpine, don’t plan on crowding into a full cabin. If winds are calm and the snow is chalky enough not to shear, it might be time to pile in. Tricky avalanche conditions? You’re going to have to wait. “Our team knows how to farm snow using snow fences, the right amount of skier compaction at the right time, and the right amount of avalanche control,” says Middleton. “We will have more skiers on the peak in good conditions, but we’ve accounted for that as well. You would never know it when the snowpack is deep, but we’ve excavated the switchback road in such a way that it will hold snow even in extended dry and windy conditions. The last thing anyone—even ski mountaineers—wants to encounter at these slope angles is what amounts to an icy groomer.”

The cars were built in Austria and traveled by ship, train, and truck to Big Sky. The resort kept them under wraps until the big reveal. At press time, the ski area was planning on a grand opening for the new Tram on December 19th, 2023. Photography by Chris Kamman, Courtesy of Big Sky Resort

A Chinook helicopter’s max external payload is 28,000 pounds. But because thin air reduces lift, that’s not true at 12,000 feet. For a stock Chinook with a full load of gas and crew, the max payload at the top of Lone Mountain drops well under 10,000 pounds. In order to hoist the 13,000 pound generator or even the 9,000 pound tower crane parts shown here, the pilot had to get creative. “We put these former military Chinook CH-47D helicopters on a weight loss program when we receive them,” says PJ Helicopters’ CH-47D Flight Program Manager Brent Keeler. “All nonessential equipment and wiring is removed, which adds up to a significant weight savings. The LZ to the top of the mountain is only about two miles so we plan our fuel load for what is required for the lift—plus reserves. Our crew generally consists of two pilots and a crew chief. So, with the weight savings, careful fuel planning, and only essential crew, we can lift over 13,000 pounds at 11,166 feet on a cold day!”

The Most Noble Way Possible“A Chinook helicopter’s max external payload is 28,000 pounds. But because thin air reduces lift, that’s not true at 12,000 feet…. We put these former military Chinook CH-47D helicopters on a weight loss program when we receive them.”

Brent Keeler, PJ Helicopters’ CH-47D Flight Program Manager

Amidst a sea of grief, Big Sky’s Kimbie and Kevin Noble have turned to art and photography as a path forward.

Tanner Noble was 18, about to start his freshman year at the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he planned to study aerospace engineering. He was a bright, outdoorsy kid who ran high school cross country and loved to snowboard, mountain bike, and fly fish. He died suddenly of an undiagnosed heart condition while riding his mountain bike with friends at Big Sky Resort in the summer of 2017. From that horrific moment onward, the Noble Family, Kevin, Kimbie, and their daughter, Ashley, now 30, had to figure out a way to continue living in a world without Tanner.

When tragedy strikes and grief settles in, it can feel hard to move. Heavy, dark days turn into months, and nothing seems to relieve the sadness. Despite what people say, time often doesn’t alleviate grief of this degree; in fact it can get worse once others have moved on and society has expected you to heal. Many days over the past six years have felt that way for the Noble family of Big Sky.

“When I get sad, I go to the park. Nobody is out there. It’s freezing. I feel more whole, even though nobody is around. That’s where I go to find peace and hope.”

Kevin Noble

In the years since Tanner’s death, Kevin has found himself drawn to the blankest, coldest, most rugged landscape he could find: Yellowstone National Park in winter. “When I get sad, I go to the park,” Kevin, who now works as a professional fine art photographer, said recently from their home in Bozeman. “Nobody is out there. It’s freezing. I feel more whole, even though nobody is around. That’s where I go to find peace and hope.” The irony is not lost on Kevin that such a harsh environment somehow brings him warmth and belonging.

Growing up on the East Coast, Kevin’s parents would load him and his five siblings into a pop-up campervan each summer and head west, where they’d explore Yellowstone and the surrounding wild lands. Later, after his parents split up, Kevin’s dad took him fly fishing in Montana for weeks at a time. As a high school student, Kevin’s favorite class was photography, where he learned to develop film in his school’s darkroom. He had no idea at the time that one day he would combine his love of Yellowstone with his passion for photography in an attempt to heal.

“I’m a minimalist by nature. I aim to reduce noise— whether it’s in life or art. Less is more.”

Kevin Noble

Kevin brings his camera on those winter pilgrimages to Yellowstone to capture images of wolves and grizzlies in stark, snowy fields. “I’m a minimalist by nature. I aim to reduce noise—whether it’s in life or art,” he says. “Less is more. I don’t shoot herds of animals. It’s usually a single animal, and I use negative space as much as possible.

When Kevin and Kimble started their own family— son, Tanner, and daughter, Ashley— they, too, brought their kids to Big Sky from their home in Houston, Texas, for long stretches each summer and winter. They purchased a home on a plot of land in Big Sky over a decade ago as a getaway that quickly felt like home.

During their travels, Kimbie and Kevin would ask Tanner, “Are you more mountains or beach?” Their tenacious son never flinched in his response. “I’m 100 percent mountains, zero percent beach,” Tanner would say. When they’d travel to the beaches of Florida, Tanner, who was constantly in motion, would pace around, saying: “What are we going to do, just go sit on the beach?” Tanner thrived in the mountains, where he could explore trails on his bike, camp with friends, and run 10 miles a day.

For years, Kevin owned and ran a business based in Houston that handled litigation support for law firms. It was a vibrant company that he helped grow to several hundred employees before selling the business in 2017. “The plan was, when I turned 50 I was going to sell the company and we would move to Montana full-time and I’d do fine art photography,” says Kevin. “All that happened just a few months before Tanner died.”

To capture the bison image “40 Below,” Kevin and Kimbie awoke to the that same temperature in YNP. The van wouldn’t start and all the warning lights in Kimbie’s car lit up when they got it going. For the shot, Kevin placed a remote camera behind the car and waited for the bison to come to it.

Their plans changed drastically. “Everyone grieves differently,” Kevin says. “For me, there was no place I’d rather be than our home in Big Sky. But Kimbie was the opposite.”

For Kimbie, being in the home where Tanner spent his last days was too much. She couldn’t step foot in the house, so she kept her distance from Big Sky. “It was hard because I was in denial. I didn’t want to accept it,” Kimbie says. “Everything in Big Sky reminded me of Tanner and I kept thinking he was going to come through the door.”

Around that time, Kevin was headed into Yellowstone National Park on a winter day and he called Kimbie, who was still at their former home in Texas, and said, “What should I shoot today?” “Show me something I haven’t seen before,” she said.

“The trick is to show someone something they haven’t seen or something they have seen but in a new way.”

Kevin Noble

That’s what Kevin still aims to do. “In Yellowstone, everything has been photographed before,” he says. “The trick is to show someone something they haven’t seen or something they have seen but in a new way.”

Kimbie painted in oil earlier in her career. Now she works in a special acrylic that’s as thick as cake frosting. Photograph by WKP

“On sad days, the color would bring me up, lighten my mood, my mental state.”

Kimbie Noble

In 2020, Kevin longed to be in Montana full-time, so the couple came up with a compromise. They’d move to Bozeman, a different world than the one Tanner inhabited, but still close enough to feel the essence of him. “Little did I know, once we got to Bozeman, I would be inspired to paint again,” says Kimble. “On sad days, the color would bring me up, lighten my mood, my mental state.”

Kimbie in the Big Sky gallery. Her frequent road trips with Kevin into Yellowstone, where she drives so he can locate wildlife, inspires her work, too. Photograph by WKP

Kimbie’s howling wolf work was inspired by one of Kevin’s images. Photograph by WKP

“I wanted to try something completely unknown.”

Kimbie Noble

Kimbie grew up on the California coast and studied graphic design, then business and accounting. She put her love of art to the side, to be picked up again much later when she would need a way to manage her grief. Once she moved to Bozeman, she discovered palette knives and thick acrylic paint and started creating dimensional impressionist art inspired by the Montana landscape. She favors thickly painted, brightly colored canvases of bison in the field, Old Faithful erupting, and blooming wildflowers. “I wanted to try something completely unknown,” Kimbie says. “That’s kind of Kevin’s and my motto.”

Once they were both creating art, Kevin had the idea to turn their 2,400-square-foot barn at their Big Sky house into an art gallery, a space that could display the work that both Kimbie, the painter, and Kevin, the photographer, were now pouring much of their energy into.

When Kevin planned an opening gala for their private art showroom in Big Sky in 2021, there was just one problem: Kimbie wasn’t sure she could attend. She still hadn’t stepped foot on their Big Sky property since Tanner had passed four years and 32 days prior. To Kimbie, standing on those hallowed grounds—Tanner’s favorite place in the world—would feel like saying goodbye all over again. But then, on the night of the gallery opening, Kimbie’s thinking shifted. “I wanted to honor Tanner by sharing his love and what he meant to me,” Kimbie says through tears. “If I never came back, people would never know what a great person he was.” When she pulled into the driveway and locked eyes with Kevin that night, they both began to cry.

The Noble’s Big Sky gallery is open for private showings and events.The Noble’s Bozeman gallery, shown here, is also worth a visit.

These days, Kevin spends close to 100 days a year in Yellowstone, most of those in winter. On bitter January days, he’s often the only person camping at Mammoth Campground, the only campsite open year-round within the park. He rises early—4 or 5 a.m.—to photograph a single bison, or bobcat, or elk. The images he shoots are somber and striking, elegant in their black-and-white simplicity. “When I see something beautiful,” says Kevin, “I do think that there’s a higher purpose here. This amount of beauty cannot be by accident.”

“When I see something beautiful. I do think that there’s a higher purpose here. This amount of beauty cannot be by accident.”

Kevin Noble

The couple is in the process of opening a new second-floor gallery space on Main Street in Bozeman that will house a sun- lit studio for Kimbie to paint. “Creating art has brought me so much joy, so much healing,” Kimbie says. “It’s the subject; the freedom of the palette knives. I listen to music and let myself be absorbed in the paint and not think about anything but the present.”

The Noble’s Big Sky gallery is open for private showings and events.The Noble’s Bozeman gallery, shown here, is also worth a visit.

In memory of Tanner, the Noble family founded the Live Noble Foundation, which supports outdoor programming like biking and running races and youth organizations that get kids into the outdoors. They also helped construct a new trail, called Tanner’s Way, which connects Big Sky’s Town Center to the North Fork Trail and has an easement along the edge of the Noble family’s property.

Kimbie and Kevin Noble on the easement they created to Tanner’s Way Trailhead.

Before the ribbon cutting ceremony for the new trail, Kevin went to the grain store and asked for a bag of wildflower seeds to plant along the side of the trail. When he got back to the house, he decided one bag wasn’t enough. He bought a second bag. “We asked everyone who showed up at the ribbon cutting to walk the trail and plant flowers on each side in the fresh dirt,” says Kevin. “It’ll take a few years, but soon, you’ll ride Tanner’s Way and see wildflowers on either side.” The trail officially opened in August 2022, five years after Tanner’s death.

Wildflowers on Tanner’s Way trail.

“All my inspiration comes from this place, from Big Sky and the mountains. I’m so happy I can make art inspired by Tanner’s favorite place.”

Kimbie Noble

Today, when Kimbie and Kevin see natural beauty they are reminded of their son’s electric smile and the way he profusely shared his love and his time. Those memories now drive their art. The pain doesn’t go away, but some of the joy that a lost loved one brought to life can return. “All my inspiration comes from this place, from Big Sky and the mountains,” says Kimbie. “I’m so happy I can make art inspired by Tanner’s favorite place.”

Tanner’s Way trail.

A brief history of Big Sky from the canyon to the peak.

…the ski area came first and the development followed.

At destinations like Telluride and Breckenridge, ski mountains sprung up around nineteenth century mining towns with colorful histories and main streets lined with Victorian storefronts. Big Sky evolved differently. The vision for the resort started with simple geography: As any skier would recognize, Lone Mountain, a dramatic dacite laccolith that dominates the surrounding landscape with steep pitches up high and gentle flanks down low, is well suited to skiing. Which is why, in Big Sky, the ski area came first and the development followed.

And while there’s deeper history in this area now known as Big Sky, which is defined by a meadow and a solitary peak with strong shoulders, it’s a story of a landscape so rugged that prior to the Homestead Act there was little human activity on the lands around Big Sky. American Indian tribes camped and hunted along the river, but they never settled. And even after homesteaders put down stakes to scratch out a living, Big Sky had fewer than 50 residents for nearly a hundred years. Given the population density of Big Sky today—and the thousands of people who flock here in summer and winter—it’s hard to imagine that the federal government went to so much trouble to entice people to come to Montana, from land grants to the railroads to offering 160 acres to homesteaders for a song. Herewith, a timeline of the history of the land around Big Sky.

Pre-written history to the mid-1800s: Early Uses of the Land

Long before Lewis and Clark named the Gallatin River for Albert Gallatin, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury who financed their expedition, Native American hunter-gatherers passed through the canyon, camping along the Gallatin River. In the mid-1800s, a tribe of Indians—in Montana, native people refer to themselves as American Indians—called the Tukudeka or Mountain Sheepeaters frequented the area, hunting bighorn sheep with bows made from their horns. They were mountain hunters who moved from Wyoming’s Wind River Range west to Idaho as their mood and the animals they depended on determined.

Historians note there was a well-used Indian camp near where the Conoco station sits today. It was destroyed by prospectors in the 1890s. In his book,“The Gallatin Way to Yellowstone,” Duncan Patten describes indigenous use of the canyons dating back to the Paleo-Indian period (BCE 6000), including archaeological sites in the West Fork. “You can find obsidian chips around Big Sky, especially in the spring when the gophers are digging around,” says Barbara Rowley, author of an upcoming Assouline-brand luxury coffee table book that will commemorate 50 years of Big Sky. Native Americans would chip pieces from the obsidian cliffs in what is now Yellowstone National Park to make arrowheads.

Before settlers, European fur trappers came through Big Sky in the mid-1800s. “They depleted the beaver population and moved on to more productive rivers,” Patten writes. Up until this point, humans passed through the meadow under the mountain—but as far as science and history know, none settled permanently. Gallatin Canyon at that time was narrow and rugged, making it difficult to navigate, and the high country was too brutal for winter life.

The late 1800s: Teddy Roosevelt and Homesteaders Arrive

“It was a big black bear with that white spot under its throat. [Teddy] looked into the bear’s mouth and saw those four big tusks and said, ‘I see now how they tear up logs and trees. Just look at those tusks.”

Charles Marble, Writer, “Fifty Years in and around Yellowstone Park.”

Teddy Roosevelt hunted big game near present day Big Sky in September of 1886 with Charles Marble, who wrote about the excursion in “Fifty Years in and around Yellowstone Park.” Teddy, who was still 15 years away from the White House, shot his first bear during the 40-day expedition. “It was a big black bear with that white spot under its throat,” Marble wrote. “[Teddy] looked into the bear’s mouth and saw those four big tusks and said, ‘I see now how they tear up logs and trees. Just look at those tusks,” After camping on the West Fork of the Madison River, they crossed into Jack Creek Park and camped for several days near the Spanish Peaks Range.

Prior to Teddy’s visit, President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law in 1862, which gave settlers 160 acres of land to lure them to the western territories, including the flat meadow where Big Sky Meadow Village sits today. Given the inhospitable landscape, the promise of free land drew only the hardiest of pioneers.

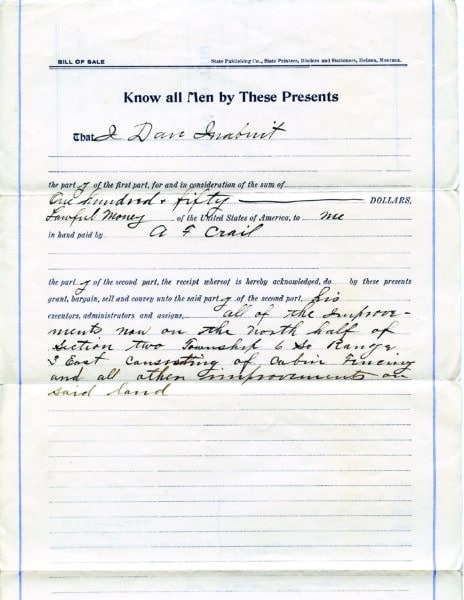

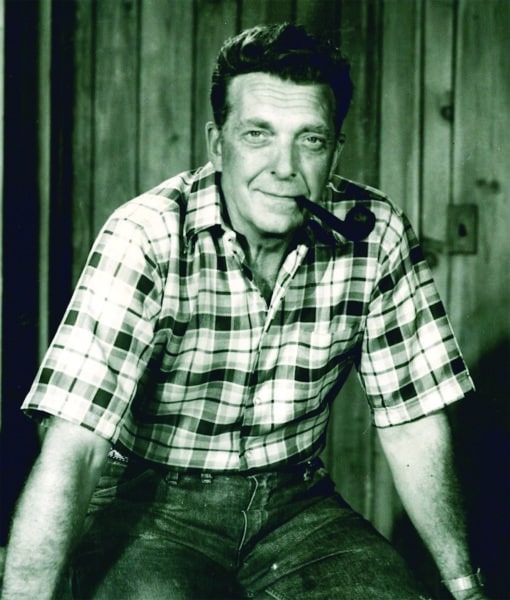

Augustus Franklin Crail Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

In 1901, Augustus Franklin Crail purchased a 160-acre parcel from homesteader Daniel Inabnit for less than $1 an acre. Back then, the property featured a forge, sawmill, piggery, and hay barns. Crail built his log cabins using a double dovetail joinery that made the structures sturdy enough to withstand Big Sky winters. More than a century later, two of the cabins remain on the property as the Crail Ranch Homestead Museum. The family first ranched sheep and cattle and grew Red Fife, a resilient wheat varietal that traces its history to the Ukraine. The Crails dubbed their variant Crail Fife. It could weather the harsh high-altitude climate.

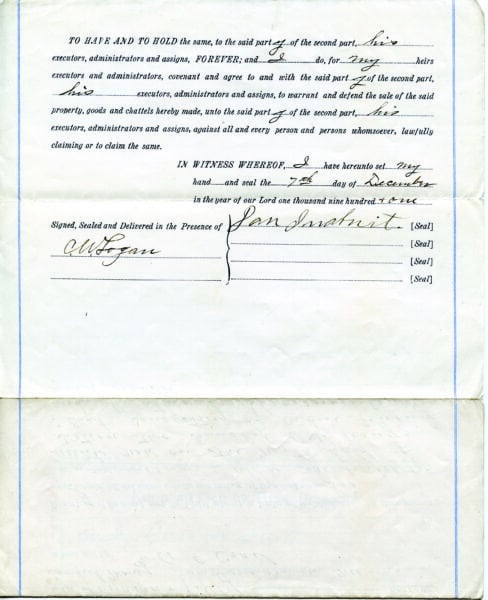

Front and back of bill of sale to Frank Crail purchasing 160 acres in Big Sky at $150 in 1901. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

Sheep grazing in Big Sky during the early 1900s. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

Late 1800s to early 1900s: In Search of Gold

“Tom was a geologist, and he figured there would be gold here like there was in Virginia City.”

Joan Traylor, Retired Ophir school teacher, fifth generation Montanan, and armchair-historian.

In 1886, Tom Michener and his family settled just down the road from the Crail property, where the Soldier’s Chapel now sits. A cattle rancher and a prospector, Michener was sure the upper basin held untapped mineral riches—and he was not alone. The 1911 edition of Mining Science suggested the area’s claims were promising. “As a result of the recent gold find … in the West Gallatin Canyon, in Montana, all of the available land clear up to the Yellowstone National Park line has been staked out by gold seekers. The most attractive propositions lie in the old channel of the river, a short distance from the West Fork of the Gallatin.”

Michener formed the West Fork Mining Company and sold stock options for the Hercules Dredging Company. Another prospector, a German named Andrew Levinski, owned claims from Middle Fork to Lone Mountain, including a copper mine near the base of what is now Big Sky Resort. But by 1917, his registrations on the copper mine had lapsed, and two of Michener’s partners, who had “reposted” Levinski’s unworked claims, arrived at the mine. A gunfight ensued, and Levinski shot and killed both of Michener’s men. His cabin full of bullet holes, Levinski was acquitted of murder charges on the basis of self-defense and claim jumping. A few years later he disappeared under mysterious circumstances—many suspect foul play.

One of the area’s most legendary figures, he’s memorialized by Lake Levinski, near the entrance to Big Sky, and more recently, by Levinski Lodge, the resort’s newest base-area workforce housing.

Although many of the early settlers were involved in prospecting—establishing claims in search of gold, tungsten, copper, or asbestos— significant mineral riches never materialized.

They used placer mining—a technique that employs water to separate eroded minerals like gold from sand or gravel—but the gold was so fine it floated through the sluices. “Tom was a geologist, and he figured there would be gold here like there was in Virginia City,” says Joan Traylor, a retired Ophir school teacher, fifth- generation Montanan, and armchair-historian. “But, as we like to say, it didn’t pan out.”

With the gold rush a bust, the upper basin remained sparsely populated at best. In 1910, a census-taker named Henry Cowherd trudged through the land now known as Big Sky and counted just 47 souls living in 18 households— including five Crails and five Micheners.

In 1910, a census-taker named Henry Cowherd trudged through the land now known as Big Sky and counted just 47 souls living in 18 households—including five Crails and five Micheners.

In the late 1990s, the Michener property was sold and Traylor, who is dedicated to historical preservation, was instrumental in dismantling and moving the only salvageable building to the grounds of the Ophir School. She’s now spearheading an effort to move the Michener cabin once more, this time to the Crail Ranch property where the public can walk the ranch, wander trails, visit the community garden, and learn about Big Sky’s past. “The history of the Crails and the Micheners is intertwined,” she says, “and Crail Ranch is the only acre in Big Sky that’s truly dedicated to history.”

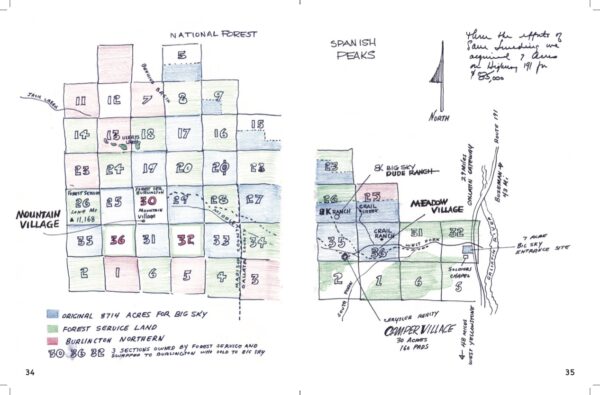

Ed Homer’s sketched map of checkered land plot allocations. Photo from the book by Ed Homer, “Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

1860s to 1992: Railroads and a Checkered Past

“Big Sky’s land ownership and history is most directly tied to the railroads. All this land that today goes for millions of dollars, they couldn’t give it away.”

Barbara Rowley, Author

The story of how the private land around Big Sky changed hands over the years starts with a complex checkerboard that dates back to 1864, the year President Lincoln inked the Northern Pacific Railroad charter. In order to incentivize the railroad to build new tracks, the government granted the railroad 46 million acres of land from Minnesota to Oregon— much of it in Montana.

“Big Sky’s land ownership and history is most directly tied to the railroads,” Rowley says. “All this land that today goes for millions of dollars, they couldn’t give it away.” The land was divided up in a checkerboard. “It didn’t have anything to do with the topography. It was just chopped up into 640 (acre) squares,” she says. The Northern Pacific Railroad expanded into Bozeman in 1883, but no tracks were ever built in the Gallatin Canyon. Still, the land in the upper basin was valuable for its dense groves of pine. The railroad needed timber for railroad ties—every mile of track needed 2,500 crossties. Logging camps were established on Taylor Fork, and from there the cut logs would float down Taylor Fork to the Gallatin River, destined for mills downstream. The government granted the railroads eery other section of land around Big Sky, alternating with National Forest Service land and homesteads.

To access the timber, primitive logging roads were built in the canyon, which ranchers then used in summer to drive cattle and sheep to the meadows. But the land was still sparsely populated. By 1940, the census recorded only 40 people living in what would become Big Sky, dropping by seven people over three decades. Back then, there were no roads up to the land where Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight Basin sit.

In 1989, Burlington Northern, which was as much a timber company as a railroad in Montana, spun off the timber outfit Plum Creek. In 1992, Plum Creek sold the land to Tim Blixseth, who also came from the timber industry. Over those many decades, the land that now houses Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight continued to be logged extensively.

Breaking a log jam on the Gallatin. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

“Way back then, Tom Michener knew the value of tourism. He had pamphlets printed up that he sent back east to rally visitors… to escape their urban stress.”

Joan Traylor

Early 1900s to 1960s: Dude Ranching: City Slickers Channel Their Inner Cowboy

CR Dude Ranch. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

Although the Crails continued to ranch on the land for some 50 years—first raising herds of sheep and then cattle—many of the upper basin’s residents turned to dude ranching in the early 1900s to entice visitors bound for Yellowstone National Park to extend their itinerary. These early entrepreneurs knew what others would discover 70 years later: Tourism was the real motherlode for the upper basin. “Way back then, Tom Michener knew the value of tourism,” Traylor says. “He had pamphlets printed up that he sent back east to rally visitors to come out to Montana and escape their urban stress.”

Starting in 1927, the B Bar K, known today as the Lone Mountain Ranch, was run as a dude ranch. The property has had different uses and owners over the years, from a boy’s camp to a logging camp to headquarters for Chet Huntley (more on him in a minute) and execs from Chrysler and Conoco during Big Sky’s startup. Today, with lodgepole guest cabins dating back to 1927, it’s a premier cross-country ski destination and dude ranch with sleigh rides, weekly rodeos, and horseback riding.

In the 1950s, Patten, whose family owns Black Butte Ranch near West Yellowstone, worked as a wrangler at Elkhorn Ranch. “I was in college at the time, and it was the best damn life a kid could have…. People came from urban centers to experience the Western way of life. You’d get to be a cowboy and ride a horse.” But then, like now, Yellowstone was also a draw. “When I was a wrangler, they’d ask us to drive guests down to Yellowstone for the day. It was always on Sundays, my day off.”

Patten remembers the days before skiing arrived. “Up by Big Sky, you had timber in the mountains and grazing in the valley. That was it,” he says. “Back then, there were about seven families living there. Dude ranching was the main thing in the ’50s. You had Covered Wagon Ranch, 320, Elkhorn, and 9 Quarter Circle.”

1920s to 1950s: Gallatin Gateway to Yellowstone

Yellowstone was established as a national park in 1872, with maybe 1,000 visitors a year showing up in its first decade. Numbers rose to a whopping 13,727 visitors in 1904. In 2021, 4.8 million people passed through Yellowstone’s gates. “The railroad played a major role in the opening up of Yellowstone Park,” Patten says. In the 1920s, the railroads battled for market share to deliver visitors to Yellowstone from different directions. “Everybody was competing with everybody else to get into Yellowstone,” he says.

In 1925, the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad ran an electric spur line into Salesville, Montana, and built the Gallatin Gateway Inn, a luxury hotel with a telephone in every room. According to Patten, the railroads promoted the canyon as a gateway to Yellowstone and even convinced locals to rename the town of Salesville to “Gallatin Gateway.” Thousands of visitors were bused through the canyon from the hotel to the west gate of the park. “When the road was still gravel, they’d need to back cars up the hills in low gear to prevent overheating,” Patten says. In the mid-1930s, the road was paved with a basic asphalt called “road-oil,” making travel from Gallatin Gateway to the park a fair bit smoother.

These days, history repeats itself. Many of the roughly one million cars that drive through the canyon each year are headed for West Yellowstone, and, not unlike the dude ranches from a century ago, Big Sky serves as a resort gateway to the park. Visitors come to Big Sky to fly fish, hike, and golf, but they’ll add a day or two in the park to their itinerary. To accommodate, companies like Karst Stage run daily shuttles to the park in summer.

“We’re a gateway for the park,” says Kristin Kern, Huntley’s niece and owner of the Hungry Moose groceries in Big Sky. “In summer, we make 75 to 100 sandwiches a day for people who are getting picked up in Big Sky and going on tours to Yellowstone.” But modern visitors to Big Sky find a resort transformed. “Even in the ’40s and ’50s, the dude ranch cabins had no electricity or water. We used kerosene lamps to read at night. It was pretty rustic,” Patten says.

1970 to 1974: Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Dream

“Nothing I’ve ever done, or seen, or accomplished— including [watching] Alan Shepard’s first space ride from Cape Canaveral— compares to my happiness in launching Big Sky.”

Chet Huntley

From 1956 to 1970, Chet Huntley co-anchored NBC’s nightly news program with David Brinkley, attaining celebrity on par with John Wayne and The Beatles. But before he was a broadcast icon covering war, elections, and assassinations, Huntley was a third-generation Montanan. He was born in a railroad depot in Cardwell, Montana (his father was a telegraph operator for the railroads). “He really did have a lot of Montana manure on his boots,” quipped The New York Times in 1974.

Chet Huntley, news anchor and founder of Big Sky Resort. Photograph courtesy of Kristin Kern

Huntley often returned to Montana to fish and ride horses. Using connections he made through NBC, he partnered with a handful of investors including the Chrysler Realty Corporation to develop a ski resort on Lone Mountain. Huntley promised Big Sky would be “the greatest thing that ever happened to Montana.” He meant not only great skiing, but a thriving economy from a clean industry. In August of 1969, Huntley asked Montana Governor Forrest Anderson to let him use the name “Big Sky of Montana” for his new ski resort. He had to ask for permission because Pulitzer Prize- winning author A.B. “Bud” Guthrie, who penned the novel “The Big Sky” in 1947, had given the rights to the state of Montana. “That’s when the governor picked up the phone and instructed [secretary of state] Frank Murray to give Chet the “Big Sky” name,” writes Ed Homer, a Chrysler VP who worked closely with Huntley, in his sketchbook, “Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

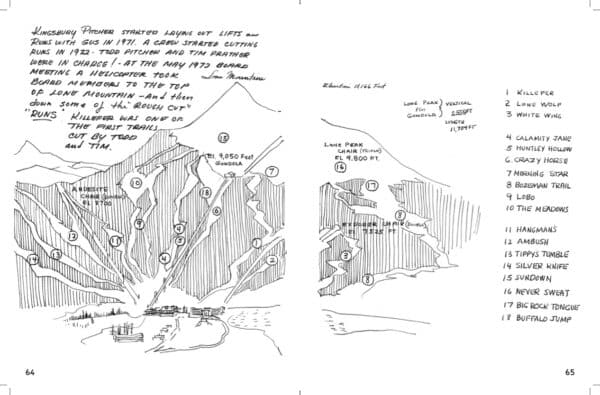

Ed Homer’s sketched map of the original ski trails in 1970. Image from the book by Ed Homer,” Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

Homer describes that time when the idea for Big Sky was coalescing. After a tour up Lone Mountain in 1970, the Big Sky board of directors had their first meeting and elected Huntley as the chairman. “Nothing I’ve ever done, or seen, or accomplished—including [watching] Alan Shepard’s first space ride from Cape Canaveral— compares to my happiness in launching Big Sky,” Huntley said.

In the 1970s, Huntley and his investors bought former homestead properties from private landowners, including the Crail property, and acquired other parcels from Burlington Northern as part of a series of hotly contested land exchanges between the railroad and the United States Forest Service.

The resort opened in the fall of 1973, with four lifts—Andesite, Explorer, Lone Peak, and a gondola. The runs Huntley’s Hollow and Tippy’s Tumble were named for the resort’s first couple. Before the runs were cut, French Olympic ski racer Jean-Claude Killy had been dropped in by helicopter to assess the bowl on Lone Mountain and the slopes on Andesite. He proclaimed the skiing “magnifique!”

In the ensuing decades, much of the private land now occupied by Yellowstone Club, Moonlight Basin, and Spanish Peaks was still owned by Burlington Northern’s spin-off timber company, Plum Creek, which clear-cut the land to the ground. Another series of land swaps in the mid- ’90s by developers created a continuous swath of private land for development. Today, Lone Mountain Land Company is dedicated to restoring the environment as it manages old-growth forest and clear rivers— and the wildlife that depends on that habitat.

1976 to 2023: Everett Kircher and the Modern Resort

In 1976, ski area pioneer Everett Kircher, owner of Michigan- based Boyne Resorts, bought Big Sky for $8.5 million. Like Huntley, Kircher saw the promise of Lone Mountain to the future of skiing. “He was really in love with skiing and the ski business, and a ski resort out West was a long-held dream,” says Molly Kircher, Everett Kircher’s daughter-in-law and Senior VP of Brand Development at Boyne USA. The Kirchers inherited the Huntley Lodge as part of the original sale and built condominium hotels, but the development of the privately owned land around the resort was and is outside of their purview. “Everett Kircher’s focus was skiing,” she says. “The Lone Mountain Ranch was part of the sale, but he declined to buy it at the time. He was concerned that it was going to take focus away from the ski area.” Today, when a hotel goes up near Big Sky, the ski area sees it as a boon. “As we grow, we always need more of a bed base and more restaurants, activities, and amenities for our guests,” says Kircher.

Modern-day Big Sky Resort. Photograph by Kene Sperry

2000 to 2023: Finally, a Town Center

In 1970, three years before the bull wheels started turning at Big Sky, Bob Simkins, whose family opened a lumberyard in West Yellowstone in 1945, predicted that the flat expanse of land where the Big Sky Town Center now sits would someday be valuable. He and Jim Taylor bought (and swapped land for) six square miles from the owners of Sappington Ranch. A second generation of Simkins inherited the land after Bob died in 1993, but it remained undeveloped until the early 2000s. Since then, the 165-acre walkable development, under ownership by Lone Mountain Land Company since 2022, has evolved into a downtown district filled with shops, restaurants, community events, and a hotel.

Present Day: A Dream Realized and Modern Times

In February 1974, just one month before Chet Huntley would pass away, a small group of board members skied up to his home. “I suddenly realized…the Big Sky dream had indeed come true,” Homer wrote in his sketchbook. As they looked out at Andesite and Lone Mountain, Huntley pointed out that, with binoculars, you could see the skiers. “It was Chet’s simple, honest, and direct way of expressing his fulfillment at seeing people…enjoying themselves at Big Sky—people and nature, sharing together.” Chet Huntley succumbed to lung cancer just three days before the official grand opening celebration of Big Sky, but those who knew him say it wasn’t tragic timing. He’d already seen his dream realized.

Today the land where Sheepeaters dropped obsidian arrowheads and where generations of timber companies clear-cut square-shaped parcels has become neighborhoods and a town. The Kirchers continue to modernize the ski area with a new tram to the summit this season, complete with an all-glass viewing platform to capture the views. And in the meadow, where hardy homesteaders and ranchers eked out a living, Town Center is growing up. While some dude ranches remain, nobody ever struck it rich on gold, and ranching was a tough existence at this elevation. But as some of the visionaries foresaw, tourism sustained a community that grew from a settlement to a town.

What might Huntley think of Big Sky’s development today? “People ask me that all the time,” says Kern. “If I had to channel Chet, I think he’d be so excited about the fact that so many people come here to recreate. His entire plan was to share Montana with people.”

How The Mountain To Meadow Trail Became LegendaryWhen the original Mountain to Meadow trail opened in 2015, it was deemed pretty darn great. It turned out that connecting the ski area to Town Center via mildly bermed singletrack was a good idea. In short order, what was conceived as a multi-use trail was quickly adopted by mountain bikers—and pretty much only mountain bikers. “It didn’t take long for people to realize it was an incredible bike trail,” says Pete Costain, who designed M2M and oversaw construction on behalf of Lone Mountain Land Company through the business he founded—Terraflow Trails. “Mountain bikers made it their own. It was a fun ride.”

The Mountain to Meadow story could have ended there, if not for happenstance. A new development was going in between town and the ski hill, and about 80 percent of M2M was going to be erased. The Lone Mountain Land Company, in partnership with the Big Sky Community Organization which oversees the trail network, saw this not as a problem but as an opportunity, and was promptly back on the phone with Costain and Terraflow. “Pete, we need a reroute,” was what they said. “Oh, and we’re creating a permanent easement on some Spanish Peaks land to make it happen.”

For trail builders, reroutes are improvements. Knowing that the original M2M had been embraced by mountain bikers, Pete was free to design version two as a purist’s, purpose-built, directional mountain bike trail. The new M2M would be even more accessible to less skilled riders, but it would also feature what Pete calls “sniper lines,” little spurs with kickers and drops to satisfy experts. Because it was a directional trail—no uphill traffic on the obvious descent—it could be ridden at a range of speeds. On the roller coaster flats you could pump yourself back up to top speed.

“If you’re trying to create a destination worthy trail, it should really stand out. It shouldn’t be just more legacy- style singletrack.” -Pete Costain, Owner of Terraflow Trails

Parkin Costain buffing some beautiful dirt. Photograph by Pete Costain

All this is in keeping with the types of trails Terraflow builds around Montana and Washington State. Some people describe them as “backcountry flow” trails. By design they incorporate natural trail elements like rocks and roots, but in other sections the trails also include the type of machine-built berms you might find at a ski area bike park. You can roll the jumps if you like, or send them. It’s a rollicking mashup of old-school and new.

“If you’re trying to create a destination worthy trail, it should really stand out,” says Pete. “It shouldn’t be just more legacy-style singletrack. Mountain bikers want to feel as though they’re being catered to. I’m a huge fan of directional trails like Mountain to Meadow. The negative is that a community like Big Sky has to raise more funds to also build trails for hikers and walkers. But new bike technology and the popularity of mountain biking mean that most people are riding really fast now. You want the confidence to know that you aren’t going to come upon a hiker or a horseback rider on their way up.”

Trailwork equals long days. Photograph by Pete Costain

Stacking rock outside of a berm. Photograph by Pete Costain

“We thankfully manage a lot of the land so we can give the easements, and we work with the other property owners.” -Bayard Dominick, Lone Mountain Land Company’s Vice President of Planning & Development

Destination riders expect bermed turns. Photograph by Pete Costain

“Teamwork makes the dream work.”—Pete Costain. Photograph by Pete Costain

The jumps are there if you want them. Or just roll. Photograph by Pete Costain

On public lands, this type of new trail construction takes years. Bayard Dominick, Lone Mountain Land Company’s Vice President of Planning and Development says, “We thankfully manage a lot of the land so we can give the easements, and we work with other property owners. We’ve been really successful gaining access and moving quickly with trails.”

And they aren’t done yet. Pete’s crew just roughed in a new section to Uplands that will be perfect in the spring after the winter snow compacts it. “The more trails and public open space that we can fit in the better,” he says. “With a little bit of pedaling you can now ride from Moonlight to Mountain to Meadow and continue on all the way down to the high school.”

Which gets us back to why the new Mountain to Meadow trail is earning legendary status in Montana and beyond. Pete built the trail in sections (old and new) with natural stopping points that make you gather with friends and scream, “That was sick!” But ultimately, it’s the connection itself that is seeing mountain bikers from around the region seek out this standout trail.

“They rip the trail and then they catch live music. It’s what a mountain community is all about.” -Pete Costain, Owner of Terraflow Trails

Photograph by Jonathan Finch

“On Thursday evenings in summer,” says Pete, “you see people up from Bozeman, or from town riding or shuttling to the start of Mountain to Meadow. Riders rip the trail to catch live music in Town Center. It’s what a mountain community is all about. Just watching people having this much fun is rewarding. It’s the reason why the Lone Mountain Land Company is commissioning this work.”

Need proof that the Big Sky Curling League is the hot winter event on a Friday night? Well, the sport’s popularity has soared so high that the longtime favorite, Trivia Night, had to abandon Friday due to dwindling attendance and switch to another night of the week. As for Broomball, the powerhouse non-gravity sport of mountain towns everywhere, it quickly went out of vogue once curling appeared, and appears to have exited the Big Sky scene.

Don’t take that to mean that Big Sky’s curlers are elitists like Canadian curlers. Jeff Trulen, who helped bring this sport of kings and Wisconsin beer drinkers to Big Sky and now oversees management of the all important ice, is the first to recognize that curling in Big Sky is still a bit rough. For one, it takes place outside, which only happens in Canada and the Midwest for special promotions—like the NHL’s Winter Classic, but with less fisticuffs and more teeth.

“When we started,” says Jeff, “the ice was not anything to be proud of. The concert venue that became the ice rink wasn’t flat. There would be ten inches of ice on one side and two inches on the other end with grass poking through, and every time it warmed up a little we had to cancel. For curling, the Zamboni is an imperfect ice finisher.”

With the addition of a chilled concrete slab a few years back, things got better for the local curlers. But it’s still not exactly a premium venue. The big curling clubs flood their ice and use hand tools to finish it to a mirror-like gloss. They would crack a bottle of Leinenkugel over the head of anyone that dared to skate on it. The Big Sky lanes, meanwhile, are set on shared skating ice. And yes, the curling still happens outside.

But to back up. In those dark days before Big Sky Curling, the hockey league was hoping to get more people using the ice so they could help pay for the Zamboni. Jeff, who has hockey kids, suggested curling. “Great idea, Jeff,” they said. “You are now in charge.”

By Big Sky standards, Jeff had a long history of curling. He’d been playing in Bozeman for two full winters. And although he never touched a hack or a rock box or a pebble head growing up, he is a native of Wisconsin. With those credentials, he became the “purchaser of stones,” a highly esteemed position that also sees Jeff placing the 44 pound stones in a trailer after competition and for the long off-season. “I became the instant guru in curling, which I was not,” says Jeff. “Then I had to teach everyone.”

Photo by Joe Esenther

In January of 2018, the first Friday Night Curling event went down with 16 teams and two sessions. Flash forward to today, and curling is such a hot ticket that the Big Sky Community Organization took over most of the logistics. Team openings are filled long before anyone thinks to advertise the opportunity. Jeff estimates that 90 to 95 percent of the people he taught to curl are still active. This season on Friday nights at the rink, 24 teams of four will sweep in front of rocks on four lanes over two sessions. The last curler to walk off the ice will do so around midnight. Jeff and BSCO get there two hours early at four o’clock to prep the surface. He doesn’t take offense when visiting Canucks stop and say: “That’s not proper curling. That’s just throwing stones, like we would do on a pond.”

“Some people take it seriously. But curling in Big Sky is mostly a chance for developers to hang with lifties and have a beer with realtors and line cooks.” -Jeff Trulen, Big Sky resident who started the curling league in Big Sky

Photo by Joe Esenther

As the Canadians walk off shaking their heads, Jeff cracks a beer. “Some people take it seriously,” says Jeff. “But curling in Big Sky is mostly a chance for developers to hang with lifties and have a beer with realtors and line cooks.”

The league has become a community hangout. Come down and cheer on the “Big Sky Rocks,” or team “I Swept With Your Wife.” The all-woman team in faux fur is the “Slippery Beavers.” They are a fan favorite.