Big Sky, Montana

A brief history of Big Sky from the canyon to the peak.

…the ski area came first and the development followed.

At destinations like Telluride and Breckenridge, ski mountains sprung up around nineteenth century mining towns with colorful histories and main streets lined with Victorian storefronts. Big Sky evolved differently. The vision for the resort started with simple geography: As any skier would recognize, Lone Mountain, a dramatic dacite laccolith that dominates the surrounding landscape with steep pitches up high and gentle flanks down low, is well suited to skiing. Which is why, in Big Sky, the ski area came first and the development followed.

And while there’s deeper history in this area now known as Big Sky, which is defined by a meadow and a solitary peak with strong shoulders, it’s a story of a landscape so rugged that prior to the Homestead Act there was little human activity on the lands around Big Sky. American Indian tribes camped and hunted along the river, but they never settled. And even after homesteaders put down stakes to scratch out a living, Big Sky had fewer than 50 residents for nearly a hundred years. Given the population density of Big Sky today—and the thousands of people who flock here in summer and winter—it’s hard to imagine that the federal government went to so much trouble to entice people to come to Montana, from land grants to the railroads to offering 160 acres to homesteaders for a song. Herewith, a timeline of the history of the land around Big Sky.

Pre-written history to the mid-1800s: Early Uses of the Land

Long before Lewis and Clark named the Gallatin River for Albert Gallatin, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury who financed their expedition, Native American hunter-gatherers passed through the canyon, camping along the Gallatin River. In the mid-1800s, a tribe of Indians—in Montana, native people refer to themselves as American Indians—called the Tukudeka or Mountain Sheepeaters frequented the area, hunting bighorn sheep with bows made from their horns. They were mountain hunters who moved from Wyoming’s Wind River Range west to Idaho as their mood and the animals they depended on determined.

Historians note there was a well-used Indian camp near where the Conoco station sits today. It was destroyed by prospectors in the 1890s. In his book,“The Gallatin Way to Yellowstone,” Duncan Patten describes indigenous use of the canyons dating back to the Paleo-Indian period (BCE 6000), including archaeological sites in the West Fork. “You can find obsidian chips around Big Sky, especially in the spring when the gophers are digging around,” says Barbara Rowley, author of an upcoming Assouline-brand luxury coffee table book that will commemorate 50 years of Big Sky. Native Americans would chip pieces from the obsidian cliffs in what is now Yellowstone National Park to make arrowheads.

Before settlers, European fur trappers came through Big Sky in the mid-1800s. “They depleted the beaver population and moved on to more productive rivers,” Patten writes. Up until this point, humans passed through the meadow under the mountain—but as far as science and history know, none settled permanently. Gallatin Canyon at that time was narrow and rugged, making it difficult to navigate, and the high country was too brutal for winter life.

The late 1800s: Teddy Roosevelt and Homesteaders Arrive

“It was a big black bear with that white spot under its throat. [Teddy] looked into the bear’s mouth and saw those four big tusks and said, ‘I see now how they tear up logs and trees. Just look at those tusks.”

Charles Marble, Writer, “Fifty Years in and around Yellowstone Park.”

Teddy Roosevelt hunted big game near present day Big Sky in September of 1886 with Charles Marble, who wrote about the excursion in “Fifty Years in and around Yellowstone Park.” Teddy, who was still 15 years away from the White House, shot his first bear during the 40-day expedition. “It was a big black bear with that white spot under its throat,” Marble wrote. “[Teddy] looked into the bear’s mouth and saw those four big tusks and said, ‘I see now how they tear up logs and trees. Just look at those tusks,” After camping on the West Fork of the Madison River, they crossed into Jack Creek Park and camped for several days near the Spanish Peaks Range.

Prior to Teddy’s visit, President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law in 1862, which gave settlers 160 acres of land to lure them to the western territories, including the flat meadow where Big Sky Meadow Village sits today. Given the inhospitable landscape, the promise of free land drew only the hardiest of pioneers.

Augustus Franklin Crail Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

In 1901, Augustus Franklin Crail purchased a 160-acre parcel from homesteader Daniel Inabnit for less than $1 an acre. Back then, the property featured a forge, sawmill, piggery, and hay barns. Crail built his log cabins using a double dovetail joinery that made the structures sturdy enough to withstand Big Sky winters. More than a century later, two of the cabins remain on the property as the Crail Ranch Homestead Museum. The family first ranched sheep and cattle and grew Red Fife, a resilient wheat varietal that traces its history to the Ukraine. The Crails dubbed their variant Crail Fife. It could weather the harsh high-altitude climate.

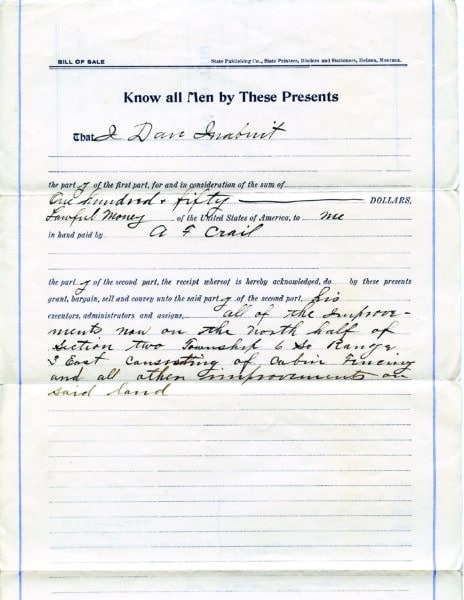

Front and back of bill of sale to Frank Crail purchasing 160 acres in Big Sky at $150 in 1901. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

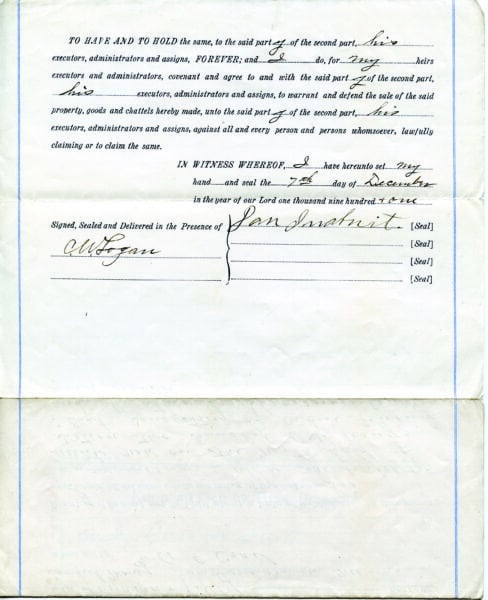

Sheep grazing in Big Sky during the early 1900s. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

Late 1800s to early 1900s: In Search of Gold

“Tom was a geologist, and he figured there would be gold here like there was in Virginia City.”

Joan Traylor, Retired Ophir school teacher, fifth generation Montanan, and armchair-historian.

In 1886, Tom Michener and his family settled just down the road from the Crail property, where the Soldier’s Chapel now sits. A cattle rancher and a prospector, Michener was sure the upper basin held untapped mineral riches—and he was not alone. The 1911 edition of Mining Science suggested the area’s claims were promising. “As a result of the recent gold find … in the West Gallatin Canyon, in Montana, all of the available land clear up to the Yellowstone National Park line has been staked out by gold seekers. The most attractive propositions lie in the old channel of the river, a short distance from the West Fork of the Gallatin.”

Michener formed the West Fork Mining Company and sold stock options for the Hercules Dredging Company. Another prospector, a German named Andrew Levinski, owned claims from Middle Fork to Lone Mountain, including a copper mine near the base of what is now Big Sky Resort. But by 1917, his registrations on the copper mine had lapsed, and two of Michener’s partners, who had “reposted” Levinski’s unworked claims, arrived at the mine. A gunfight ensued, and Levinski shot and killed both of Michener’s men. His cabin full of bullet holes, Levinski was acquitted of murder charges on the basis of self-defense and claim jumping. A few years later he disappeared under mysterious circumstances—many suspect foul play.

One of the area’s most legendary figures, he’s memorialized by Lake Levinski, near the entrance to Big Sky, and more recently, by Levinski Lodge, the resort’s newest base-area workforce housing.

Although many of the early settlers were involved in prospecting—establishing claims in search of gold, tungsten, copper, or asbestos— significant mineral riches never materialized.

They used placer mining—a technique that employs water to separate eroded minerals like gold from sand or gravel—but the gold was so fine it floated through the sluices. “Tom was a geologist, and he figured there would be gold here like there was in Virginia City,” says Joan Traylor, a retired Ophir school teacher, fifth- generation Montanan, and armchair-historian. “But, as we like to say, it didn’t pan out.”

With the gold rush a bust, the upper basin remained sparsely populated at best. In 1910, a census-taker named Henry Cowherd trudged through the land now known as Big Sky and counted just 47 souls living in 18 households— including five Crails and five Micheners.

In 1910, a census-taker named Henry Cowherd trudged through the land now known as Big Sky and counted just 47 souls living in 18 households—including five Crails and five Micheners.

In the late 1990s, the Michener property was sold and Traylor, who is dedicated to historical preservation, was instrumental in dismantling and moving the only salvageable building to the grounds of the Ophir School. She’s now spearheading an effort to move the Michener cabin once more, this time to the Crail Ranch property where the public can walk the ranch, wander trails, visit the community garden, and learn about Big Sky’s past. “The history of the Crails and the Micheners is intertwined,” she says, “and Crail Ranch is the only acre in Big Sky that’s truly dedicated to history.”

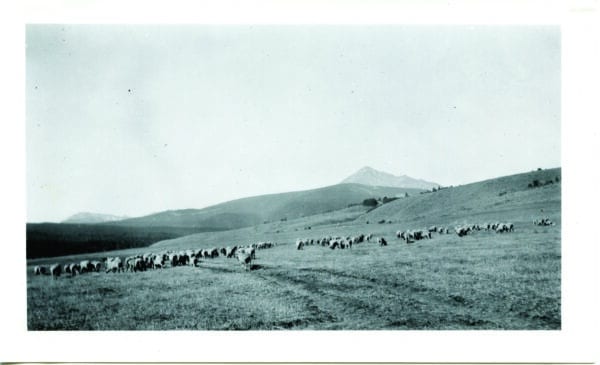

Ed Homer’s sketched map of checkered land plot allocations. Photo from the book by Ed Homer, “Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

1860s to 1992: Railroads and a Checkered Past

“Big Sky’s land ownership and history is most directly tied to the railroads. All this land that today goes for millions of dollars, they couldn’t give it away.”

Barbara Rowley, Author

The story of how the private land around Big Sky changed hands over the years starts with a complex checkerboard that dates back to 1864, the year President Lincoln inked the Northern Pacific Railroad charter. In order to incentivize the railroad to build new tracks, the government granted the railroad 46 million acres of land from Minnesota to Oregon— much of it in Montana.

“Big Sky’s land ownership and history is most directly tied to the railroads,” Rowley says. “All this land that today goes for millions of dollars, they couldn’t give it away.” The land was divided up in a checkerboard. “It didn’t have anything to do with the topography. It was just chopped up into 640 (acre) squares,” she says. The Northern Pacific Railroad expanded into Bozeman in 1883, but no tracks were ever built in the Gallatin Canyon. Still, the land in the upper basin was valuable for its dense groves of pine. The railroad needed timber for railroad ties—every mile of track needed 2,500 crossties. Logging camps were established on Taylor Fork, and from there the cut logs would float down Taylor Fork to the Gallatin River, destined for mills downstream. The government granted the railroads eery other section of land around Big Sky, alternating with National Forest Service land and homesteads.

To access the timber, primitive logging roads were built in the canyon, which ranchers then used in summer to drive cattle and sheep to the meadows. But the land was still sparsely populated. By 1940, the census recorded only 40 people living in what would become Big Sky, dropping by seven people over three decades. Back then, there were no roads up to the land where Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight Basin sit.

In 1989, Burlington Northern, which was as much a timber company as a railroad in Montana, spun off the timber outfit Plum Creek. In 1992, Plum Creek sold the land to Tim Blixseth, who also came from the timber industry. Over those many decades, the land that now houses Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight continued to be logged extensively.

Breaking a log jam on the Gallatin. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

“Way back then, Tom Michener knew the value of tourism. He had pamphlets printed up that he sent back east to rally visitors… to escape their urban stress.”

Joan Traylor

Early 1900s to 1960s: Dude Ranching: City Slickers Channel Their Inner Cowboy

CR Dude Ranch. Photograph courtesy of Historic Crail Ranch Museum

Although the Crails continued to ranch on the land for some 50 years—first raising herds of sheep and then cattle—many of the upper basin’s residents turned to dude ranching in the early 1900s to entice visitors bound for Yellowstone National Park to extend their itinerary. These early entrepreneurs knew what others would discover 70 years later: Tourism was the real motherlode for the upper basin. “Way back then, Tom Michener knew the value of tourism,” Traylor says. “He had pamphlets printed up that he sent back east to rally visitors to come out to Montana and escape their urban stress.”

Starting in 1927, the B Bar K, known today as the Lone Mountain Ranch, was run as a dude ranch. The property has had different uses and owners over the years, from a boy’s camp to a logging camp to headquarters for Chet Huntley (more on him in a minute) and execs from Chrysler and Conoco during Big Sky’s startup. Today, with lodgepole guest cabins dating back to 1927, it’s a premier cross-country ski destination and dude ranch with sleigh rides, weekly rodeos, and horseback riding.

In the 1950s, Patten, whose family owns Black Butte Ranch near West Yellowstone, worked as a wrangler at Elkhorn Ranch. “I was in college at the time, and it was the best damn life a kid could have…. People came from urban centers to experience the Western way of life. You’d get to be a cowboy and ride a horse.” But then, like now, Yellowstone was also a draw. “When I was a wrangler, they’d ask us to drive guests down to Yellowstone for the day. It was always on Sundays, my day off.”

Patten remembers the days before skiing arrived. “Up by Big Sky, you had timber in the mountains and grazing in the valley. That was it,” he says. “Back then, there were about seven families living there. Dude ranching was the main thing in the ’50s. You had Covered Wagon Ranch, 320, Elkhorn, and 9 Quarter Circle.”

1920s to 1950s: Gallatin Gateway to Yellowstone

Yellowstone was established as a national park in 1872, with maybe 1,000 visitors a year showing up in its first decade. Numbers rose to a whopping 13,727 visitors in 1904. In 2021, 4.8 million people passed through Yellowstone’s gates. “The railroad played a major role in the opening up of Yellowstone Park,” Patten says. In the 1920s, the railroads battled for market share to deliver visitors to Yellowstone from different directions. “Everybody was competing with everybody else to get into Yellowstone,” he says.

In 1925, the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad ran an electric spur line into Salesville, Montana, and built the Gallatin Gateway Inn, a luxury hotel with a telephone in every room. According to Patten, the railroads promoted the canyon as a gateway to Yellowstone and even convinced locals to rename the town of Salesville to “Gallatin Gateway.” Thousands of visitors were bused through the canyon from the hotel to the west gate of the park. “When the road was still gravel, they’d need to back cars up the hills in low gear to prevent overheating,” Patten says. In the mid-1930s, the road was paved with a basic asphalt called “road-oil,” making travel from Gallatin Gateway to the park a fair bit smoother.

These days, history repeats itself. Many of the roughly one million cars that drive through the canyon each year are headed for West Yellowstone, and, not unlike the dude ranches from a century ago, Big Sky serves as a resort gateway to the park. Visitors come to Big Sky to fly fish, hike, and golf, but they’ll add a day or two in the park to their itinerary. To accommodate, companies like Karst Stage run daily shuttles to the park in summer.

“We’re a gateway for the park,” says Kristin Kern, Huntley’s niece and owner of the Hungry Moose groceries in Big Sky. “In summer, we make 75 to 100 sandwiches a day for people who are getting picked up in Big Sky and going on tours to Yellowstone.” But modern visitors to Big Sky find a resort transformed. “Even in the ’40s and ’50s, the dude ranch cabins had no electricity or water. We used kerosene lamps to read at night. It was pretty rustic,” Patten says.

1970 to 1974: Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Dream

“Nothing I’ve ever done, or seen, or accomplished— including [watching] Alan Shepard’s first space ride from Cape Canaveral— compares to my happiness in launching Big Sky.”

Chet Huntley

From 1956 to 1970, Chet Huntley co-anchored NBC’s nightly news program with David Brinkley, attaining celebrity on par with John Wayne and The Beatles. But before he was a broadcast icon covering war, elections, and assassinations, Huntley was a third-generation Montanan. He was born in a railroad depot in Cardwell, Montana (his father was a telegraph operator for the railroads). “He really did have a lot of Montana manure on his boots,” quipped The New York Times in 1974.

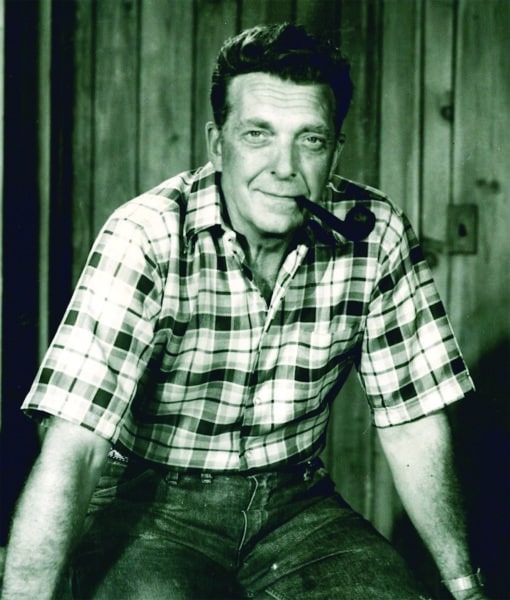

Chet Huntley, news anchor and founder of Big Sky Resort. Photograph courtesy of Kristin Kern

Huntley often returned to Montana to fish and ride horses. Using connections he made through NBC, he partnered with a handful of investors including the Chrysler Realty Corporation to develop a ski resort on Lone Mountain. Huntley promised Big Sky would be “the greatest thing that ever happened to Montana.” He meant not only great skiing, but a thriving economy from a clean industry. In August of 1969, Huntley asked Montana Governor Forrest Anderson to let him use the name “Big Sky of Montana” for his new ski resort. He had to ask for permission because Pulitzer Prize- winning author A.B. “Bud” Guthrie, who penned the novel “The Big Sky” in 1947, had given the rights to the state of Montana. “That’s when the governor picked up the phone and instructed [secretary of state] Frank Murray to give Chet the “Big Sky” name,” writes Ed Homer, a Chrysler VP who worked closely with Huntley, in his sketchbook, “Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

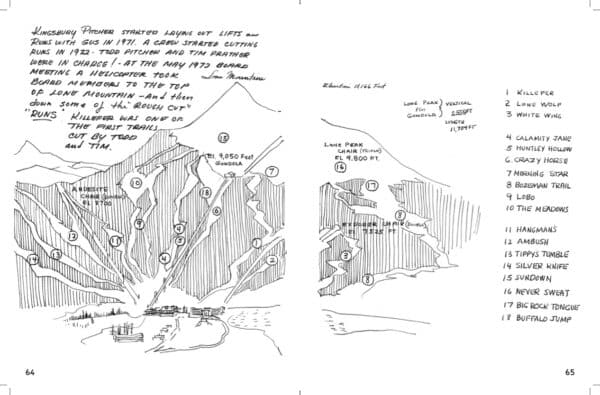

Ed Homer’s sketched map of the original ski trails in 1970. Image from the book by Ed Homer,” Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

Homer describes that time when the idea for Big Sky was coalescing. After a tour up Lone Mountain in 1970, the Big Sky board of directors had their first meeting and elected Huntley as the chairman. “Nothing I’ve ever done, or seen, or accomplished—including [watching] Alan Shepard’s first space ride from Cape Canaveral— compares to my happiness in launching Big Sky,” Huntley said.

In the 1970s, Huntley and his investors bought former homestead properties from private landowners, including the Crail property, and acquired other parcels from Burlington Northern as part of a series of hotly contested land exchanges between the railroad and the United States Forest Service.

The resort opened in the fall of 1973, with four lifts—Andesite, Explorer, Lone Peak, and a gondola. The runs Huntley’s Hollow and Tippy’s Tumble were named for the resort’s first couple. Before the runs were cut, French Olympic ski racer Jean-Claude Killy had been dropped in by helicopter to assess the bowl on Lone Mountain and the slopes on Andesite. He proclaimed the skiing “magnifique!”

In the ensuing decades, much of the private land now occupied by Yellowstone Club, Moonlight Basin, and Spanish Peaks was still owned by Burlington Northern’s spin-off timber company, Plum Creek, which clear-cut the land to the ground. Another series of land swaps in the mid- ’90s by developers created a continuous swath of private land for development. Today, Lone Mountain Land Company is dedicated to restoring the environment as it manages old-growth forest and clear rivers— and the wildlife that depends on that habitat.

1976 to 2023: Everett Kircher and the Modern Resort

In 1976, ski area pioneer Everett Kircher, owner of Michigan- based Boyne Resorts, bought Big Sky for $8.5 million. Like Huntley, Kircher saw the promise of Lone Mountain to the future of skiing. “He was really in love with skiing and the ski business, and a ski resort out West was a long-held dream,” says Molly Kircher, Everett Kircher’s daughter-in-law and Senior VP of Brand Development at Boyne USA. The Kirchers inherited the Huntley Lodge as part of the original sale and built condominium hotels, but the development of the privately owned land around the resort was and is outside of their purview. “Everett Kircher’s focus was skiing,” she says. “The Lone Mountain Ranch was part of the sale, but he declined to buy it at the time. He was concerned that it was going to take focus away from the ski area.” Today, when a hotel goes up near Big Sky, the ski area sees it as a boon. “As we grow, we always need more of a bed base and more restaurants, activities, and amenities for our guests,” says Kircher.

Modern-day Big Sky Resort. Photograph by Kene Sperry

2000 to 2023: Finally, a Town Center

In 1970, three years before the bull wheels started turning at Big Sky, Bob Simkins, whose family opened a lumberyard in West Yellowstone in 1945, predicted that the flat expanse of land where the Big Sky Town Center now sits would someday be valuable. He and Jim Taylor bought (and swapped land for) six square miles from the owners of Sappington Ranch. A second generation of Simkins inherited the land after Bob died in 1993, but it remained undeveloped until the early 2000s. Since then, the 165-acre walkable development, under ownership by Lone Mountain Land Company since 2022, has evolved into a downtown district filled with shops, restaurants, community events, and a hotel.

Present Day: A Dream Realized and Modern Times

In February 1974, just one month before Chet Huntley would pass away, a small group of board members skied up to his home. “I suddenly realized…the Big Sky dream had indeed come true,” Homer wrote in his sketchbook. As they looked out at Andesite and Lone Mountain, Huntley pointed out that, with binoculars, you could see the skiers. “It was Chet’s simple, honest, and direct way of expressing his fulfillment at seeing people…enjoying themselves at Big Sky—people and nature, sharing together.” Chet Huntley succumbed to lung cancer just three days before the official grand opening celebration of Big Sky, but those who knew him say it wasn’t tragic timing. He’d already seen his dream realized.

Today the land where Sheepeaters dropped obsidian arrowheads and where generations of timber companies clear-cut square-shaped parcels has become neighborhoods and a town. The Kirchers continue to modernize the ski area with a new tram to the summit this season, complete with an all-glass viewing platform to capture the views. And in the meadow, where hardy homesteaders and ranchers eked out a living, Town Center is growing up. While some dude ranches remain, nobody ever struck it rich on gold, and ranching was a tough existence at this elevation. But as some of the visionaries foresaw, tourism sustained a community that grew from a settlement to a town.

What might Huntley think of Big Sky’s development today? “People ask me that all the time,” says Kern. “If I had to channel Chet, I think he’d be so excited about the fact that so many people come here to recreate. His entire plan was to share Montana with people.”

How The Mountain To Meadow Trail Became LegendaryWhen the original Mountain to Meadow trail opened in 2015, it was deemed pretty darn great. It turned out that connecting the ski area to Town Center via mildly bermed singletrack was a good idea. In short order, what was conceived as a multi-use trail was quickly adopted by mountain bikers—and pretty much only mountain bikers. “It didn’t take long for people to realize it was an incredible bike trail,” says Pete Costain, who designed M2M and oversaw construction on behalf of Lone Mountain Land Company through the business he founded—Terraflow Trails. “Mountain bikers made it their own. It was a fun ride.”

The Mountain to Meadow story could have ended there, if not for happenstance. A new development was going in between town and the ski hill, and about 80 percent of M2M was going to be erased. The Lone Mountain Land Company, in partnership with the Big Sky Community Organization which oversees the trail network, saw this not as a problem but as an opportunity, and was promptly back on the phone with Costain and Terraflow. “Pete, we need a reroute,” was what they said. “Oh, and we’re creating a permanent easement on some Spanish Peaks land to make it happen.”

For trail builders, reroutes are improvements. Knowing that the original M2M had been embraced by mountain bikers, Pete was free to design version two as a purist’s, purpose-built, directional mountain bike trail. The new M2M would be even more accessible to less skilled riders, but it would also feature what Pete calls “sniper lines,” little spurs with kickers and drops to satisfy experts. Because it was a directional trail—no uphill traffic on the obvious descent—it could be ridden at a range of speeds. On the roller coaster flats you could pump yourself back up to top speed.

“If you’re trying to create a destination worthy trail, it should really stand out. It shouldn’t be just more legacy- style singletrack.” -Pete Costain, Owner of Terraflow Trails

Parkin Costain buffing some beautiful dirt. Photograph by Pete Costain

All this is in keeping with the types of trails Terraflow builds around Montana and Washington State. Some people describe them as “backcountry flow” trails. By design they incorporate natural trail elements like rocks and roots, but in other sections the trails also include the type of machine-built berms you might find at a ski area bike park. You can roll the jumps if you like, or send them. It’s a rollicking mashup of old-school and new.

“If you’re trying to create a destination worthy trail, it should really stand out,” says Pete. “It shouldn’t be just more legacy-style singletrack. Mountain bikers want to feel as though they’re being catered to. I’m a huge fan of directional trails like Mountain to Meadow. The negative is that a community like Big Sky has to raise more funds to also build trails for hikers and walkers. But new bike technology and the popularity of mountain biking mean that most people are riding really fast now. You want the confidence to know that you aren’t going to come upon a hiker or a horseback rider on their way up.”

Trailwork equals long days. Photograph by Pete Costain

Stacking rock outside of a berm. Photograph by Pete Costain

“We thankfully manage a lot of the land so we can give the easements, and we work with the other property owners.” -Bayard Dominick, Lone Mountain Land Company’s Vice President of Planning & Development

Destination riders expect bermed turns. Photograph by Pete Costain

“Teamwork makes the dream work.”—Pete Costain. Photograph by Pete Costain

The jumps are there if you want them. Or just roll. Photograph by Pete Costain

On public lands, this type of new trail construction takes years. Bayard Dominick, Lone Mountain Land Company’s Vice President of Planning and Development says, “We thankfully manage a lot of the land so we can give the easements, and we work with other property owners. We’ve been really successful gaining access and moving quickly with trails.”

And they aren’t done yet. Pete’s crew just roughed in a new section to Uplands that will be perfect in the spring after the winter snow compacts it. “The more trails and public open space that we can fit in the better,” he says. “With a little bit of pedaling you can now ride from Moonlight to Mountain to Meadow and continue on all the way down to the high school.”

Which gets us back to why the new Mountain to Meadow trail is earning legendary status in Montana and beyond. Pete built the trail in sections (old and new) with natural stopping points that make you gather with friends and scream, “That was sick!” But ultimately, it’s the connection itself that is seeing mountain bikers from around the region seek out this standout trail.

“They rip the trail and then they catch live music. It’s what a mountain community is all about.” -Pete Costain, Owner of Terraflow Trails

Photograph by Jonathan Finch

“On Thursday evenings in summer,” says Pete, “you see people up from Bozeman, or from town riding or shuttling to the start of Mountain to Meadow. Riders rip the trail to catch live music in Town Center. It’s what a mountain community is all about. Just watching people having this much fun is rewarding. It’s the reason why the Lone Mountain Land Company is commissioning this work.”

Need proof that the Big Sky Curling League is the hot winter event on a Friday night? Well, the sport’s popularity has soared so high that the longtime favorite, Trivia Night, had to abandon Friday due to dwindling attendance and switch to another night of the week. As for Broomball, the powerhouse non-gravity sport of mountain towns everywhere, it quickly went out of vogue once curling appeared, and appears to have exited the Big Sky scene.

Don’t take that to mean that Big Sky’s curlers are elitists like Canadian curlers. Jeff Trulen, who helped bring this sport of kings and Wisconsin beer drinkers to Big Sky and now oversees management of the all important ice, is the first to recognize that curling in Big Sky is still a bit rough. For one, it takes place outside, which only happens in Canada and the Midwest for special promotions—like the NHL’s Winter Classic, but with less fisticuffs and more teeth.

“When we started,” says Jeff, “the ice was not anything to be proud of. The concert venue that became the ice rink wasn’t flat. There would be ten inches of ice on one side and two inches on the other end with grass poking through, and every time it warmed up a little we had to cancel. For curling, the Zamboni is an imperfect ice finisher.”

With the addition of a chilled concrete slab a few years back, things got better for the local curlers. But it’s still not exactly a premium venue. The big curling clubs flood their ice and use hand tools to finish it to a mirror-like gloss. They would crack a bottle of Leinenkugel over the head of anyone that dared to skate on it. The Big Sky lanes, meanwhile, are set on shared skating ice. And yes, the curling still happens outside.

But to back up. In those dark days before Big Sky Curling, the hockey league was hoping to get more people using the ice so they could help pay for the Zamboni. Jeff, who has hockey kids, suggested curling. “Great idea, Jeff,” they said. “You are now in charge.”

By Big Sky standards, Jeff had a long history of curling. He’d been playing in Bozeman for two full winters. And although he never touched a hack or a rock box or a pebble head growing up, he is a native of Wisconsin. With those credentials, he became the “purchaser of stones,” a highly esteemed position that also sees Jeff placing the 44 pound stones in a trailer after competition and for the long off-season. “I became the instant guru in curling, which I was not,” says Jeff. “Then I had to teach everyone.”

Photo by Joe Esenther

In January of 2018, the first Friday Night Curling event went down with 16 teams and two sessions. Flash forward to today, and curling is such a hot ticket that the Big Sky Community Organization took over most of the logistics. Team openings are filled long before anyone thinks to advertise the opportunity. Jeff estimates that 90 to 95 percent of the people he taught to curl are still active. This season on Friday nights at the rink, 24 teams of four will sweep in front of rocks on four lanes over two sessions. The last curler to walk off the ice will do so around midnight. Jeff and BSCO get there two hours early at four o’clock to prep the surface. He doesn’t take offense when visiting Canucks stop and say: “That’s not proper curling. That’s just throwing stones, like we would do on a pond.”

“Some people take it seriously. But curling in Big Sky is mostly a chance for developers to hang with lifties and have a beer with realtors and line cooks.” -Jeff Trulen, Big Sky resident who started the curling league in Big Sky

Photo by Joe Esenther

As the Canadians walk off shaking their heads, Jeff cracks a beer. “Some people take it seriously,” says Jeff. “But curling in Big Sky is mostly a chance for developers to hang with lifties and have a beer with realtors and line cooks.”

The league has become a community hangout. Come down and cheer on the “Big Sky Rocks,” or team “I Swept With Your Wife.” The all-woman team in faux fur is the “Slippery Beavers.” They are a fan favorite.

How Big Sky Became an Arts Destination.

“We could be life every other resort town, but we don’t have to be.” -Katie Alvin, Development Director of the Arts Council of Big Sky

In the fall of 2018, Waldazo—a majestic life-size bison assembled from a collection of donated iron—by Bozeman sculptor Kirsten Kainz was installed in Town Center’s Fire Pit Park. Waldazo challenges viewers to question America’s throw- away culture. Photograph by Nathan Peterson

In a mountain town like Big Sky, our attention is typically drawn to athleticism—skiing, biking, running, boating—or the natural world—summits bathed in alpenglow, chance encounters with wildlife, the night sky at elevation. In that environment, happening upon art unexpectedly breaks us from our routines. In a small way it puts us in an altered state of consciousness, which lowers the heart rate and allows for reflection. Public art is another way that Big Sky connects. When it comes to the arts, says Katie Alvin, Development Director of Arts Council of Big Sky, “we could be like every other resort town, but we don’t have to be.” In Big Sky, artwork doesn’t just exist in galleries, it’s woven into the fabric of the community. Here, stakeholders believe that art builds communities. Montana, in their world view, has the potential to become an arts destination, like Vail, Colorado, or Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In October of 2018, Big Sky became the first location in Montana to install an outdoor sculpture, Winter, by renowned Montana artist Deborah Butterfield. The recipient of multiple awards, including fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts and Guggenheim, Butterfield began crafting horse sculptures out of primitive mixed-media materials in the 1970s. Her love for the equine form has resulted in gallery showings across the country and her work has graced museums like The Whitney, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian Institution. Made in Butterfield’s Montana studio, Winter was created using driftwood gathered along the banks of the Gallatin, Yellowstone, and Madison rivers, then cast in bronze and patinaed to withstand the elements. Photograph courtesy of Arts Council of Big Sky

Beyond the economic value of art, its primary benefit is in improving the lives of residents, employees, and tourists. By showcasing the work of regional and local artists, public art, says Jesine Munson, Public Art and Outreach Coordinator for Arts Council of Big Sky, lets artists and citizens engage in conversations about Big Sky’s past, present, and future.

Having lived most of his life amidst the serene beauty of the Northwest, Brad Rude’s art pays homage to the natural world that surrounds his Walla Walla studio and home. From dogs to rhinos, Rude’s sculptures often challenge viewers to see the animal world in unconventional terms. Brad’s sculpture, To The Skyland, depicts a lone wolf, alert and in motion, as it leans forward into an unknown future assisted by red wheels and a walking stick. Look for the final To The Skyland across from Town Center Plaza in 2024. Photograph by Nathan Peterson

But public art doesn’t happen without private support. In Big Sky, the arts community forged partnerships to achieve its goals. As Big Sky’s largest property owner, Lone Mountain Land Company has emerged as a key proponent for marrying art and development. “They’ve engaged the community,” says Alvin. “Lone Mountain Land Company’s shared vision of a dedicated art corridor ensures locals and visitors see not only Big Sky’s physical beauty, but its cultural history, too.”

“Lone Mountain Land Company’s shared vision of a dedicated art corridor ensures locals and visitors see not only Big Sky’s physical beauty, but its cultural history, too.” -Katie Alvin, Development Director for Arts Council of Big Sky

Today, the curated public art installments in Big Sky equate to more than $1 million in artwork acquired by citizens through community campaigns, or secured through private donations by individuals and businesses. Big Sky now boasts 11 outdoor sculptures that reflect an eclectic mix of contemporary and natural themes. The Arts Council hopes people will stumble across sculptures—and pause to reflect.

From Vermont to California, Fleming’s work has created

a “space lace” that defies linear structure and norms. “My works hint at the co-existence of the mundane and the cosmological where two realities exist including the possibility that the past is also the present,” Fleming writes. “The structures are diagrams of thought that provide a glimpse of the strangeness beyond the everyday world; opening a place where thought becomes tangible, history leaves a trace, and information exhales form.” Located at the BASE Community Center, Lightning serves as a memorial to Anne Buchanan and other lives lived and lost. Photograph by Nathan Peterson

Big Sky now boasts 11 outdoor structures that reflect an eclectic mix of contemporary and natural themes.

Combined with the Arts Council’s renewed emphasis on education, interactive maps now make it easy to learn about the artists and selection process.

The goal, says Munson, is to “select engaging art that is different, that is interactive, that makes people think.”

“The goal is to select engaging art that is different, that is interactive, that makes people think.” -Jesine Munson, Public Art & Outreach Coordinator for Arts Council of Big Sky

There’s nothing static about Big Sky, the air, light, and seasons constantly shape-shift. It’s no surprise, then, that kinetic sculptor Pedro S. De Movellán’s work, Gibbous, was selected by the Arts Council of Big Sky to grace the roundabout on Huntley Drive and Town Center Avenue. A towering sculpture made of natural hardcoat anodized aluminum, stainless steel, and painted with a bright orange automobile paint, the work’s spherical shapes and movement mirror a gibbous moon fluctuating between half full and full. According to the Davidson Gallery that represents De Movellán, his ability to harness motion through air and wind gives his work a unique and ever-changing dynamic. Photograph by Nathan Peterson

Expect to see more such work soon. Artist Brad Rude’s accessible and engaging bronze sculpture, To The Skyland, will be installed on a walking path across from Town Center Plaza in 2024. A collaboration with the Gallatin River Task Force will result in a water education mural in the newly opened Pedestrian Tunnel. The work will both celebrate the importance of Big Sky’s waterways to the physical and mental health of the community, and at the same time interpret the river as impressionistic artwork. Meanwhile, future Pollinator Pathway gardens will connect art installations while also showcasing native species.

For more information about upcoming installations and art collaborations visit: bigskyarts.org.

YELLOWSTONE CLUB TURNS RECLAIMED WATER INTO SNOW

ACCORDING TO THE GALLATIN RIVER TASK FORCE, the most cost-effective and sustainable way to address drought and protect the Gallatin River is through water conservation. In Big Sky, every gallon of water saved or reused directly contributes to the health of the river and the watershed. That’s where snowmaking with reclaimed water comes in. Man-made snow boosts the snowpack, and because it is denser than natural snow, it delays runoff in the spring, helping to keep the watershed and aquifer healthy. The Yellowstone Club project, says Rich Chandler, Director of Environmental Operations for the YC, is about water conservation and the beneficial use of a scarce resource. Chandler also notes that man-made snow from reclaimed water is safe to ski and recreate on. This winter at the YC, another 35,000 linear feet of pipe with 66 different connections to snowmaking guns will take reclaimed water from the pond on top of the golf course to make snow on 55 skiable acres. That man-made snowpack will deliver a 25 million gallon benefit to the aquifer and watershed.

LONE MOUNTAIN LAND COMPANY AND MSU BRING A TEACHING HOTEL TO CAMPUS

The Montana State University campus in Bozeman, Montana, where the Marriott Tribute Hotel will be built to further students’ careers in hospitality. Photo by Joe Esenther

MONTANA IS BOOMING, but as fast as it’s growing, the state still experiences a brain drain when its college- educated youth leave in search of work. Montana State University’s Hospitality Management program and Lone Mountain Land Company hope to help change that by developing a campus “teaching hotel.” THE VIM will be a Marriott Tribute Hotel developed by LMLC on a 40-year land lease. The hotel’s name comes from the MSU Bobcat’s fight song: “We’ve got the vim, we’re here to win.” (In the old expression “vim and vigor, vim means energy or pluck.) Once THE VIM opens, students will work alongside seasoned hoteliers as they get hands-on training in hospitality management, culinary arts, marketing, engineering, design, retail, and construction. THE VIM is expected to break ground in late 2024 or early 2025. The clientele? Visiting faculty, students, parents, alumni, and donors. Aesthetically, the hotel will honor the historic architecture of the University and downtown Bozeman with brick facades and arched windows. A rooftop Alumni Club—with its private dining bar, hot tub, cold plunge, fitness center, sauna, and steam room—will serve as a philanthropy hub. There will be discounted rates available to welcome parents and students. “With a three-meal restaurant, cafe, marketplace, and official Bobcat-themed store, MSU will not only promote their brand, but offer classes that train kids to stay and become part of Montana’s driving economic force,” says LMLC’s Vice President of Planning and Development, Bayard Dominick.

BIG SKY COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION GOES “ALL OUT” ON TRAILS AND PARKS

Biker riding one of the diverse BSCO trails.

Photograph by Tibor Nemeth

THIS PAST SUMMER, the Big Sky Community Organization (BSCO) celebrated its 25th anniversary and launched its “All Out for Parks & Trails Campaign’’ with the goal of serving residents and visitors alike. With this campaign, BSCO has three key initiatives: the creation of a new multi-use park for all ages and abilities; improving and expanding existing athletic fields and courts; and enhancing the existing trail network to ensure the safety and enjoyment of cyclists and pedestrians by building new multi-use recreational trails to meet increasing demand.

BSCO believes that community building happens through recreation. Expected to break ground in 2024 on land donated by LMLC in summer 2023, a new park will be constructed for the public off Ousel Falls Road which will repurpose six acres into a community hub. Initial plans show a dog park, lawn game area, picnic shelters, playground, and a full basketball court with a small plaza and seating. Cornhole boards with boulder seating, and a multi-use playing field suitable for everything from soccer to ultimate frisbee will round out the site. “The park will serve the entire population of Big Sky,” says BSCO CEO, Whitney Montgomery.

Existing parks will be modernized and receive a significant renovation, too. BSCO will expand the skate park and pump track to include a jump-line to practice skills. Existing athletic fields will be expanded and upgraded to provide a longer playing season, and a new adventure based, ADA accessible, playground designed for multiple ages and abilities will become a hangout for young families.

Other initiatives include adding 20 miles of multi-use recreational trails and improving in-town paths and trails to ensure a safer experience for pedestrians and cyclists. Ultimately, BSCO’s campaign will bring everyone in Big Sky “All Out”—connected, healthy, and thriving.

BIG SKY COMMUNITY PARTNERS FIND CHILDCARE SOLUTIONS

LAST SPRING, AS SCHOOL YEAR CALENDARS COUNTED DOWN, many Big Sky families were struggling to find quality, affordable childcare for the summer months. In a poll conducted by the Big Sky Child Care Task Force, more than 35 families indicated a need for childcare for four to five-year- olds. Hannah Waterbury, Executive Director of Spanish Peaks Community Foundation says that although a lack of affordable childcare is a national and statewide issue, it particularly affects Big Sky residents. She notes that more than 96 percent of women who live in Big Sky work, and those with children spend $1,733 monthly—16 percent of their median income— on childcare. Moreover, says Waterbury, the 50 percent of Big Sky’s workforce that commutes also face a need for childcare. Montana is one of only a handful of states that does not offer public pre-kindergarten. And Big Sky has only one full-time, year-round childcare facility—Morningstar Learning Center. These collective challenges make it difficult for families to live in Big Sky. They also make it hard for businesses to retain middle management employees.

Recognizing the urgency, Big Sky’s private, philanthropic, and public entities joined forces. Employing spaces donated by Big Sky School District #72, the Lone Mountain Land Company, Spanish Peaks Community Foundation, and Yellowstone Club Community Foundation worked tirelessly to launch the Big Sky Summer Camp for preschoolers.

But that was just one piece of the puzzle. “When Lone Mountain Land Company became aware of the need for childcare, they stepped in to help,” says Waterbury.

Morningstar needed more resources. Applying for a Childcare Innovation and Infrastructure Grant, funded by The American Rescue Plan Act and the Montana Department of Health and Human Services was the best option. In order to receive the $1 million dollar grant, Morningstar needed a 10 percent corporate match. That’s where LMLC was able to help. While Morningstar only ended up receiving $413,904 of its request, LMLC still matched its $100,000 commitment. The funds were the next piece of the puzzle for helping to address Big Sky’s childcare needs. Ultimately, more expansion will be necessary.

COMMUNITY HOUSING COMING TO BIG SKY

A rendering of the RiverView Place development.

Rendering courtesy of Lone Mountain Land Company

WORKING WITH MULTIPLE PARTNERS, LMLC wants to ensure that the people who work in Big Sky can also call it home. To date, hundreds of millions of dollars has been earmarked to address community housing initiatives.

RiverView Place is slated to house 387 locals in 97 units in 2024. Featuring a mix of 1, 2, and 3-bedroom apartments, as well as shared living suites, RiverView residents will find affordable housing within walking distance to amenities such as playgrounds, pickleball courts, as well as athletic fields in the Community Park and restaurants, nightlife, fitness centers, and other critical retail services in the Town Center and Meadow Village shopping districts. The deed-restricted residential development ties directly into Big Sky’s extensive trail network and features a Skyline Connect bus stop that is expected to ease vehicular traffic. The housing complex focuses on sustainable building practices with low-flow plumbing fixtures and solar panels, and even includes covered bike storage to encourage residents to consider alternate modes of transportation.

“Affordable housing in mountain towns remains a critical need without a clear solution,” says LMLC’s Cryder Bancroft. “Through collaborative partnerships with the Big Sky Housing Trust and the Resort Tax, LMLC is working to ensure anyone who works in Big Sky can also live in Big Sky.” The upcoming Gateway Village development in Gallatin Gateway will offer 323 3-and 4-bedroom units catering to workers who prefer commuting to Big Sky. Meanwhile, the design sports a mountain-modern aesthetic and Gateway Village will look and feel like a mountain community.

WINTER LIGHTS & DELIGHTS: TOWN CENTER FRIDAYS

Photograph by Joe Esenther

EXPERIENCE THE ENCHANTMENT of Big Sky Town Center every Friday between 4–7pm from December 22 to the end of March. Immerse yourself in a lively atmosphere where local retailers, restaurants, bars, and art galleries offer exclusive specials, retail raffles, local musicians, and more. Friday nights in Town Center are the place to be this winter season!

BIG SKY’S TOWN CENTER WELCOMES SIX NEW SHOPS AND RESTAURANTS

Inside the new Surefoot boot fitting store in Town Center.

Photograph by Cryder Bancroft

Town Center gets more vibrant every year. The town is already rich with well-established shopping, dining, and nightlife. This winter brings even more.

– Got nagging pains in your ski boots? A Surefoot boot fitting store is now open at 47 Town Center Ave.

– Need a top-of-the-line chef ’s knife to round out your professional kitchen? The craftspeople at the renowned New West KnifeWorks will set you up.

– Got young ones coming to town? Cut back on their screen time when they’re indoors with a visit to The Great Rocky Mountain Toy Company, a southwestern Montana standout shop from Bozeman.

– With an eye on premium men’s and women’s lifestyle and outdoor apparel, Bluebird is a must hit for your four season casual wear.

– For those who don’t want to head to the base area to load up on Big Sky Resort logo wear, you can now pop right over to the new Big Sky Resort Store in Town Center.

– All that shopping will make you hungry, which is where another Bozeman transplant, Thai Basil, comes in. The Deep Fried Tiger Bombs—crab, cream cheese, onion, green onion, and carrot deep fried in a wonton paper sound like the bomb.

These new additions add to the already 35 established Town Center restaurants, bars, outfitters, and boutiques.

A Careful Appreciation of the Porcupine

They’re big-appetite herbivores with powerful incisors similar to a beaver’s who favor a diet of tree bark, the sub-bark layer cambium, roots, and tubers.

In the pantheon of small Rocky Mountain mammals, the porcupine falls somewhere between the wee, squeaky pika foraging to the side of an alpine trail, and the raccoon raiding your garbage. Cute, but not too cute. Best avoided, but still kind of cool to encounter from a safe distance.

Will you? Porcupines are common enough around Big Sky to get a major creek and trail named for them, as everyone who has hiked or biked Porcupine Creek Trail knows. But the truth is, the North American porcupine is primarily a solitary night forager and lives much of its life up in the trees. They’re a bit elusive. “I spend a ton of time in the woods, but I rarely see them,” says Andrea Saari, cofounder of Big Sky Adventures & Tours. “It’s my dogs who have encounters. I see the aftermath— the vet bills.”

Maybe a more apt question is: Should you want to encounter a porcupine? To that we give a big, hearty, slightly qualified, yes.

That’s partly because they’re really darn cute. Sweet eyes, button nose, soft fur (yes, really). It’s also worth seeing porcupines because they’re fascinating examples of evolution. They’re big- appetite herbivores with powerful incisors similar to a beaver’s who favor a diet of tree bark, the sub-bark layer cambium, roots, and tubers. They were once blamed for causing forest loss, and in the dark days of the 1950s to the ’70s, voracious porcupines were the target of ill-advised eradication efforts.

Now, about those quills, all 30,000 of them per animal. You might not actually see them from a few yards off. When you behold a porcupine in full bushy grandeur, you’re seeing fur: a soft outer layer and a second layer for warmth. The quills, which are technically hollow hairs, lie underneath. Yes, they are incredibly sharp. No, porcupines can’t shoot them. But if you touch—or if you are a dog, sniff—a porcupine it will raise and swing its spiky weaponized tail and you’ll get a painful cluster of them in your hand or snout. Just ask Andrea’s dogs.

The quills are sharper than hypodermics, and they’re scaled and barbed like fish hooks. The quills break free of the animal upon impact, leaving a victim looking like a pin cushion. If you’re stuck, get to the ER. If it’s your pooch, get right to the vet. When quills break off inside of dogs, they can migrate for years through soft tissue, eventually endangering vital organs. If you’re way off the grid, you might want to start plucking with a Leatherman tool. Given the risks—which really should only involve our dumb canine friends— and the fact that porcupines don’t hibernate, a great way to observe them is from a chairlift adjacent to a pine forest in winter.

Doug Rand, a retired landscape architect from Gallatin Gateway, sees them fairly often eating trees around his home. He once encountered two angry porcupines in a face-off, both noses festooned with quills. “Pure agony for both.” The males fight with tooth and quill for dominance. The victor sprays the female with urine to mark her as betrothed. Doug, using a spade for a prod and staying well clear of the quills, herds them into a wooden box, and ushers them to the backcountry.

Set amid the Montana wilderness, this private golf and ski community is adding to an already impressive slate of four-season amenities

At Spanish Peaks Mountain Club in Big Sky, Mont., they say the adventures are as endless as the landscape. That’s not hyperbole. With the namesake range towering in the background, Yellowstone National Park less than an hour away, and the surrounding Big Sky country a four-season wonderland of activity, the club is a haven for adventure seekers, outdoor enthusiasts, and anyone dreaming of a life well lived in wide-open spaces.

In addition to all this the rugged region offers blue-ribbon trout streams; miles of trails for hiking, mountain biking, cross-country skiing, and horseback riding; and thousands of acres of world-class skiing and snowboarding. The 3,530-acre Spanish Peaks community offers ski-in, ski-out access to Big Sky Resort’s nearly 6,000 acres of skiable terrain; a members-only clubhouse with dining room, bar, full-service spa and fitness center, and swimming pool; a riverside outpost for fly-fishing; a mid-mountain winter dining venue; tennis and pickleball courts; a snow-tubing hill; and a year-round calendar of member-only events and experiences.

During golf season, the Tom Weiskopf course, which sits at 7,000 feet, thrills on 300 acres of gently rolling terrain. The layout fits seamlessly in the Montana wilderness, with no two fairways bordering each other. When you play the 7,193-yard course, it comes as no surprise to learn that Weiskopf designed it on horseback. But golfers enjoy the 40-mile views of Spanish Peaks and Gallatin Range, as well as Yellowstone’s Absaroka and Beartooth peaks, from golf carts, not saddles. This fall, the golf experience will expand to include a 10-hole Par-3 course designed after 10 of the late Weiskopf’s favorite holes from around the world.

Located less than an hour from the Bozeman Yellowstone International airport, Spanish Peaks offers a wide range of real estate options. You can build a home in Highlands West, buy a five-bedroom townhome next to the new Par-3 course, or go as big as the Montana sky with a five- or six-bedroom Montage Mountain Home. Or opt for one of the new, fully furnished, three- and four-bedroom offerings at The Inn Residences at Montage Big Sky. Now under construction, The Inn Residences are available in deeded, one-quarter-ownership interests and include membership at Spanish Peaks. If you’re looking to maximize time with family seasonally and enjoy Spanish Peak’s signature amenities, The Inn Residences may be the perfect opportunity.

The 2023 Men’s Health Travel AwardsSome guys like to hike, bike, climb, and surf their way through vacation. Some are ready for Ashiatsu barefoot massage, Ayurvedic meditation workshops, and all-organic juice bars at the break of dawn. Others want to skip all the pretense and just chilllll. Whoever you are and whatever brand of getaway you’re into, there’s a hotel, resort, inn, or cruise out there for you.

But the world is a big place and your bucket list no doubt gets longer every year. So, how to know where to head next? Our crack team of travel-obsessed editors, writers, and staffers did the hard work of researching, comparing, and personally vetting many of the world’s best travel destinations and experiences over the past year (ya know, for science!). No matter what flavor of vacation you’re looking for, these 79 picks are guaranteed to please.

So, pack your bags and get ready to go! This is the 2023 Men’s Health Travel Awards.

Tucked into Big Sky’s chic Spanish Peaks enclave, this poshest of posh hotels is the area’s first five-star resort. Expect world-class luxury, including no-request-is-too-much concierge service, excellent fine dining options, a solid cocktail lounge, and one of Montana’s best spas. Oh, and complimentary Cadillac ride service.

Nestled in the serene mountains of Montana, Montage Big Sky is the region’s pre-eminent luxury resort centrally located within Big Sky’s 3,530-acre Spanish Peaks enclave. The resort is home to 100 well-appointed guest rooms and suites with a premium selection of experiences for every season. While known as its world-class ski resort, this destination is just as thrilling in the summer months.

This summer, Montage Big Sky invites guests to enjoy:

• Embarking on a guided adventure hike into the Big Sky ecosystem of local wildlife, flora and fauna, and limitless exploration.

• Choosing an electric or analog mountain bike for venturing in Montana’s picturesque mountains and exploring the Spanish Peak trail system.

• Practicing backcountry and 3D archery and ax throwing in Montana’s great wilderness with the resort’s well-experienced Compass adventure guides by your side.

• Mountain boarding along diverse terrains without the need of black diamond slopes or concrete.

• Channeling the authentic spirit of the Mountain West on horseback through Montana’s mountain trails, wildflower-blanketed fields, and unspoiled wilderness.

• Yellowstone Wonders National Park tour: Journeying into the most scenic piece of Yellowstone National Park’s 2.2 million acres on a guided safari tour with moose, bighorn sheep, and elk viewings along the way!

• Exploring the rugged landscape full of wildlife moving against the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone on the resort’s Southern Yellowstone Wildlife Safari (Hayden Valley) tour led by a professional naturalist tour guide.

• 4-wheeling through Montana’s wild lands on an UTV tour for a true backcountry ride with a GPS guided, off-road, and all terrain experience.

• World-class fly fishing with access to four miles of private riverways, where thousands of rainbows, cutthroats, and Montana brown trout swim in abundance.

• Experiencing a thrilling adventure through Big Sky’s only locally owned Gallatin River whitewater rafting outfitter. Raft the Gallatin River, made famous by the movie “A River Runs Through It”.

Experience the great outdoors where adventure meets luxury at Montage Big Sky. This summer, the upscale resort transforms into an outdoor adventurer’s paradise with endless outdoor activities, from fly fishing to white water rafting, and mountain biking to safari tours to Yellowstone National Park led by professional outdoor nature guides. With these exclusive experiences, guests can immerse themselves in Montana’s stunning natural landscapes and learn something new, while absorbing breathtaking views of majestic mountains.

Big Sky leaders to teach hands-on wildlife safety‘Mobile wildlife education center’ to inform visitors, residents and workers about local wildlife, backcountry safety

Charles Johnson paces excitedly around a trailer, quizzing EBS on paw prints, scat, pelts, and the difference between antlers and horns.

More than just a trailer, it’s a “mobile wildlife education center,” Johnson says. He’s leading an effort called Wild Big Sky, which aims to bring Big Sky’s visitors, locals and workers up to speed with the needs of our forest-dwelling neighbors. Beginning this week and running indefinitely, Johnson and other trained community leaders will host pop-up wilderness education around Big Sky, quizzing and teaching curious people “to better prepare the community and tourists with practices that mitigate potential human-wildlife conflicts,” according to a Wild Big Sky press release.

The mobile wildlife education center includes animal skulls, scat molds, taxidermy and fur samples, a TV monitor showing slides to practice species identification, a remote-controlled, charging bear to practice deploying inert (non-active) bear spray, and a variety of informational printouts tailored for various audiences—from kids’ coloring books to printouts in Spanish.

Johnson is the director of security for the Spanish Peaks Mountain Club, where a grizzly sow recently lumbered across a driveway with a her cubs—a reminder that humans only recently moved into that apex predator’s ecosystem, now living together on close quarters.

He spoke with EBS in the club parking lot as he prepared to host the first of two “train the trainer” sessions, he said. Any Big Sky community member who completes Johnson’s training will be able to rent the trailer, free of charge, aside from the cost of replacing inert bear spray. Johnson hopes community leaders will bring the trailer to community and business events, employee barbecues and schools.

The second training will take place on June 12. Those interested in becoming eligible to use the trailer can email Charles Johnson for more information.

The Wild Big Sky program is comprised of local employers: Town Center, Spanish Peaks Mountain Club, Montage Big Sky, Lone Mountain Land Company, Yellowstone Club, and Moonlight Basin launched the Wild Big Sky website last year “to centralize the best information available on safe human-wildlife interactions,” the release states. The mobile wildlife education center adds a hands-on, interactive learning environment.

“I need visuals,” Johnson said, holding up fox and bobcat skulls, and distinguishing between taxidermy grouse feathers. “I need the touching; I need the sight.”

He emphasized that Wild Big Sky’s main goal is not to scare people or deter them from exploring the outdoors. Rather, the program intends to spread awareness—not just the danger of bears but also moose, the importance of proper food and waste storage, and the need to give space to animals such as calving elk, Johnson suggests. He said grizzly bears get the most attention, but safe coexistence between humans and other animals is just as crucial as Big Sky continues to grow in population and visitation.

“With the potential to reach thousands of individuals each year, we aspire to create a more informed and responsible community that prioritizes both human safety and the well-being of local wildlife. With this resource, we hope the negative interactions with wildlife become a thing of the past,” Johnson stated in the release.

Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks worked with Wild Big Sky to inform the quality of educational resources in the mobile education center. The nonprofit People and Carnivores provided a grant for the construction of the trailer, according to the release.

“The Mobile Wildlife Education Center is an innovative and practical example other resort communities should replicate to reduce human-wildlife conflicts,” stated Rosie Costain, program and communications coordinator for People and Carnivores. “It’s a win for the Big Sky community, visitors, and the local wildlife.”

“I am excited to see the impact the Big Sky community will have through their Wild Big Sky program,” stated Danielle Oyler, wildlife stewardship outreach specialist with Montana FWP. “The mobile wildlife education center will help spread the word that people living in and visiting Big Sky can be great stewards of our wildlife.”

Johnson said this is “an asset that we need” as a community. He looks forward to seeing the trailer in use at the weekly farmers market, Music in the Mountains, and at BASE.

Various horns and antlers sit on a removable shelf outside the trailer. Johnson held up two antlers and asked which belonged to a mule deer and which to a white-tailed deer. He pointed out the difference, before lifting up a black bear pelt to show how its claws differ from a grizzly’s.

As more community leaders become trained in hands-on teaching through Wild Big Sky, the trailer could become a community fixture. And most anyone who spends a few minutes at the mobile wildlife education center is apt to bring new knowledge to the outdoors, helping keep Big Sky wild.